Edward Gerrard - 115 Years of Historic British Taxidermy

One of the finest Natural History companies ever seen in Great Britain

Taxidermists | Naturalists | Osteologists | Model Makers | Furriers

Taxidermists | Naturalists | Osteologists | Model Makers | Furriers

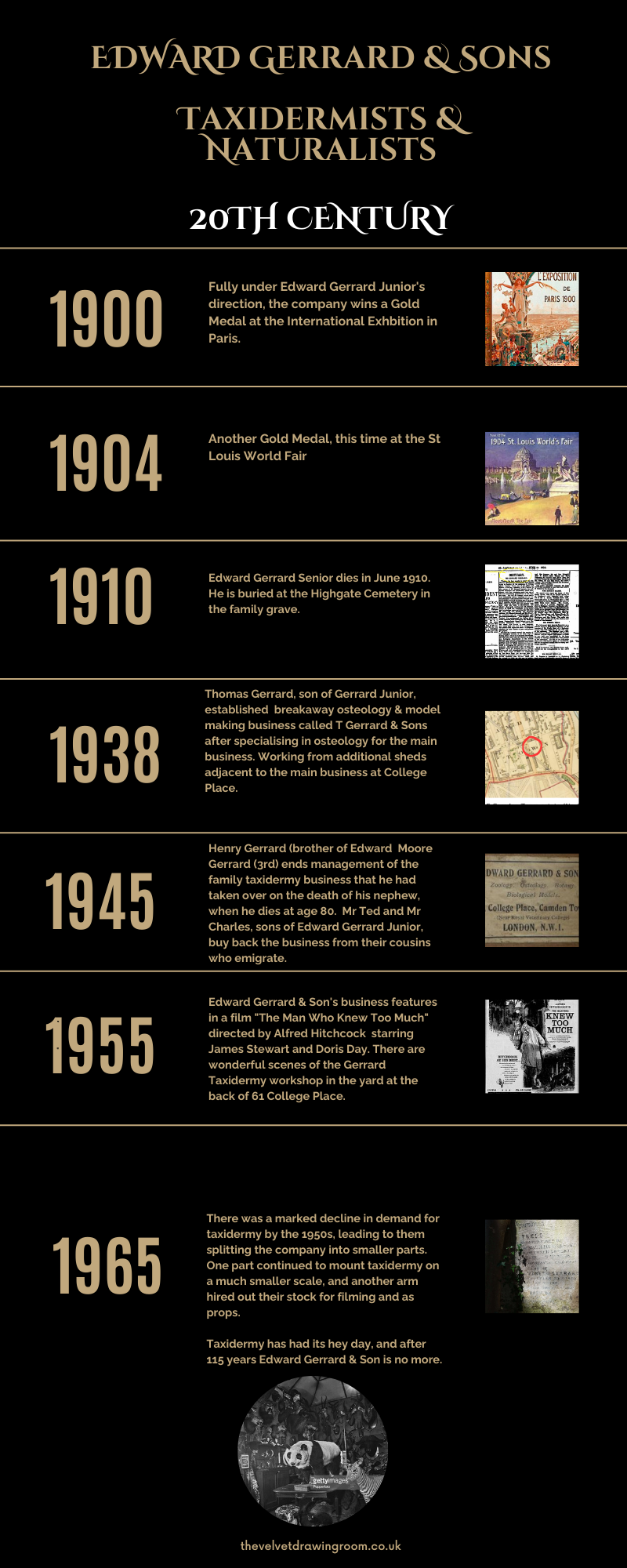

19th Century Edward Gerrard

The work and history of Edward Gerrard & Sons from the 1900s onwards is well documented, but what I was interested to find out more about was the work and origin of the company in the 19th century, the early period when the science of natural history and taxidermy were synonymous with exploration and new frontiers.

An overview of the life and work of Edward Gerrard 1810-1910

Edward Gerrard Senior

19th Century Edward Gerrard

Edward Gerrard, Taxidermist and Naturalist, was born in Oxford on 20 Oct 1810, then moved to London with his parents very soon after his birth to NW London.

His younger sister, Sarah Gerrard, was born in 1812 and died in London in 1849 at the age of just 48 yrs.

Birth, marriage and death records are not generally available earlier than about 1832, and therefore little is known about Edward’s parents, except that his mother was Ruth Eggleton (1789-1871) born in Hertfordshire and by 1951 when Edward was age 40 yrs, she was a widower.

EARLY LIFE

54 Queen Street, London N.W.

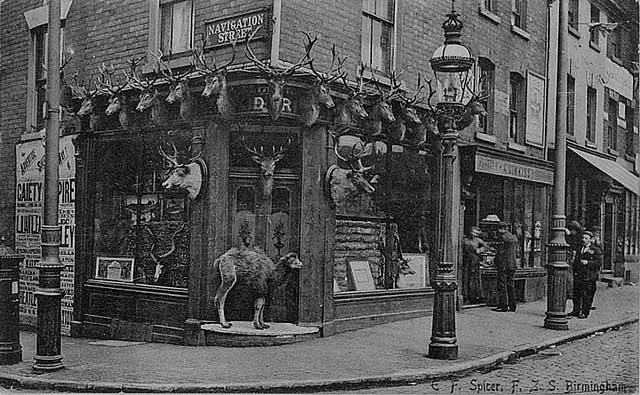

To start to look at the profile of the firm in the 19th Century of Edward Gerrard, we must first look up their earliest addresses.

The address of 54 Queen Street in Marylebone is the earliest recorded business address, or residential reference for Edward Gerrard Senior, and it’s possibly what is referred to in one or two other written accounts as the “family home”. Queen Street later became Regina Street NW1 which in modern times has entirely vanished.

From historical trade directories this address at 54 Queen Street appeared to have about half a dozen occupants, Edward Gerrard Senior being one of them, and one must deduce from this that this property had multiple residences, perhaps on different floors.

According to the 1841 census we see Edward Gerrard residing at 2 Robert Street, but we also see him advertising Queen St as his business address from 1852 (Post Office Streets Directory 1852) right up to 1884 (Post Office London Directory for Trades 1884). He would have needed a “shop front” from which to operate, and where collectors and scientists could meet.

Queen Street was the place where hunters, travellers, and naturalists came to meet and exchange or sell specimens. The proximity of London zoo and the veterinary college would later ensure a regular supply of dead animals.

Both Queen Street and Robert Street’s proximity to the workshops built as “Camden Studios” at the back of 61 College Place is also key because the Gerrard family was to operate their business from these workshops (which they also referred to in correspondence as The Natural History Studios) and to live at two addresses in College Place.

Quite contrary to the accepted narrative that the Gerrards only came to the Camden Studios in the early 1900’s this is not correct. The Gerrards workshop was at the back of 61 College Place from the mid 1800’s onwards, where they rented the “Camden Studios”. These workshops and studios were essential to the conduct of their business since taxidermy on any scale was impossible without a significantly sized workshop or series of workshops that were separate to any living quarters, and separate from their residential addresses all of which were in proximity.

1836

ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY LONDON

As a child, Gerrard said he remembered climbing over the nearby gates at Regent’s Park to chase birds and rabbits and it was this early experience that lit the flame of his interest in the natural world.

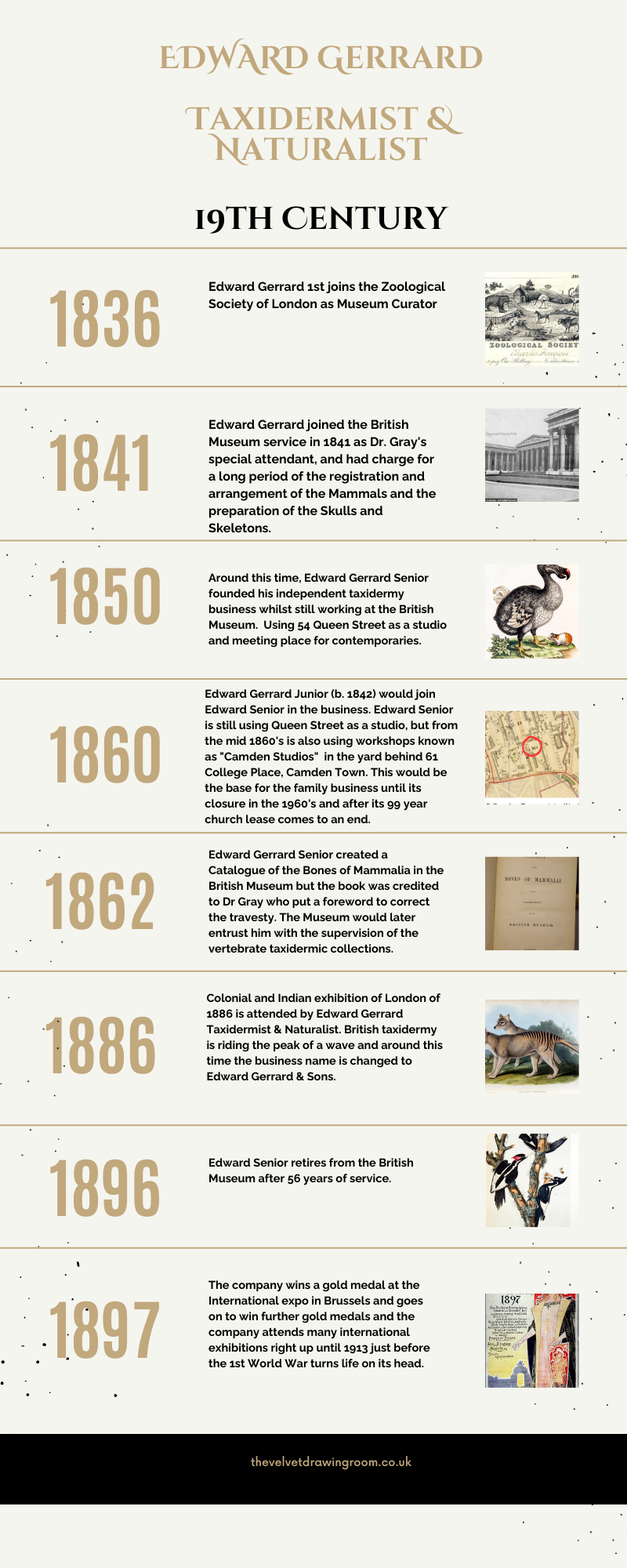

In 1836, at the age of just 26 years, Edward Gerrard Senior became the curator of the museum and resident taxidermist at the Zoological Society of London in its early days at Bruton Street. There is no information that I can find about where he learned his craft, but it is assumed he was self-taught, since he had had a lifelong interest in nature.

1837-1846

Marriage and Children

Just one year after joining the ZSL, and at the tender age of 27, Edward Gerrard Senior married Mary Ann Maltby on 28 Sept 1837 in Marylebone.

In 1840 at the age of 30 yrs his first child, Sarah E. Gerrard was born and in the following year in 1841 he moved with his wife to 2, Robert Street, NW1 (and he would live there for 15 years until 1856 after which the family moved to College Place).

His son, Edward (to become known as Edward Gerrard Junior) was born in St Pancras in 1842. (Although several published sources quote 1832 as the birth year of Edward Junior, this isn’t accurate). His daughter, Mary Ann Emma, was born in 1846. Sadly, it is recorded that his wife, Mary Ann, died in the same year, and left him a widower.

1841

The British Museum

Edward Gerrard Senior joined the Zoological Department of the British Museum in April 1841, and superintended the transfer of the Zoological collection from Great Russell street to South Kensington and assisted in arranging the specimens in the new museum. He walked across Hyde Park to and from the Museum in Bloomsbury daily, to serve under Dr. Gray, Sir Richard Owen, Dr. Gunther and Sir William Flower.

As well as being the resident taxidermist at the Museum he also curated the Osteology collection and was a member of the Linnean Society and a friend of Charles Darwin.

In 1862 he produced and edited the Catalogue of the Bones of Mammalia in the British Museum, but because of some internal politics at the Museum the book was credited to Dr Gray who wrote a foreword in the book to correct the travesty.

The Museum would later entrust Edward Gerrard Senior with the supervision of its vertebrate taxidermic collections.

A CONTEMPORANEOUS AFFAIR: THE BRITISH MUSEUM

A list of donations of mammals and birds, recorded in the British Museum’s own book “The History of the Collections of Natural History, Volume II” printed in 1906, shows that Edward Gerrard Senior made contributions to the collections alongside some of the foremost naturalists and collectors of the day, including John Gould, and the 2nd Baron Walter Rothschild.

In 1872 Dr Gray, the head of the Zoology Department at the British Museum sadly died, and after this a concerted effort was made to increase the numbers of specimens in the zoology collection.

Edward Gerrard Senior was well connected to the movers and shakers of the day. He was a friend of Darwin and was a member of the elite Linnean Society, as was Darwin. The Linnean Society of London was founded in 1878 and is the oldest extant natural history society in the world, existing solely for the furtherance of natural history. Mr Gerrard was also a buyer and purveyor of species that were being brought back from expeditions that took place as a result of the march of colonialism.

The range of locations from which the contributions from collectors and explorers came is staggering – it includes never before heard of lands and some very exotic locations including the River Amazon, Egypt, West Africa and Kathiawar, the Lower Congo, Angola and Benguela. Several of these contributions contained new species. As the years roll on, we can see how wide a footprint these collectors and agents had, and that they were exploring the world as never before.

In 1879 68 birds from Southeastern New Guinea, collected by Mr. Kendal Broadbent were purchased by the British Museum from Mr. Gerrard. In the same year 700 birds from the British Indian Empire, including several types from the Indian Museum were presented by the Secretary of State for India.

In the years 1880 and 1881 combined there were a total of 17,216 zoological items donated or sold to the British Museum from both the near and the far-flung places of the world.

GERRARD – AT THE EPICENTRE OF THE GOLDEN AGE

There is a theme emerging throughout this book published by the British Museum; the sheer number of specimens being collected is huge. After Dr. Gray, the previous Head of Zoological Department at the British Museum died, there is internally generated criticism of collecting for collecting’s sake during these years; that there was not enough curation; that the Museum was full of multiple copies of the same species, and this appears to be true. But what we have to remember is that this is the dawn of exploration and the playing out of witness to Darwin’s theory of evolution that he had first published in 1859 and that he continued to expand and detail up to his death in 1882.

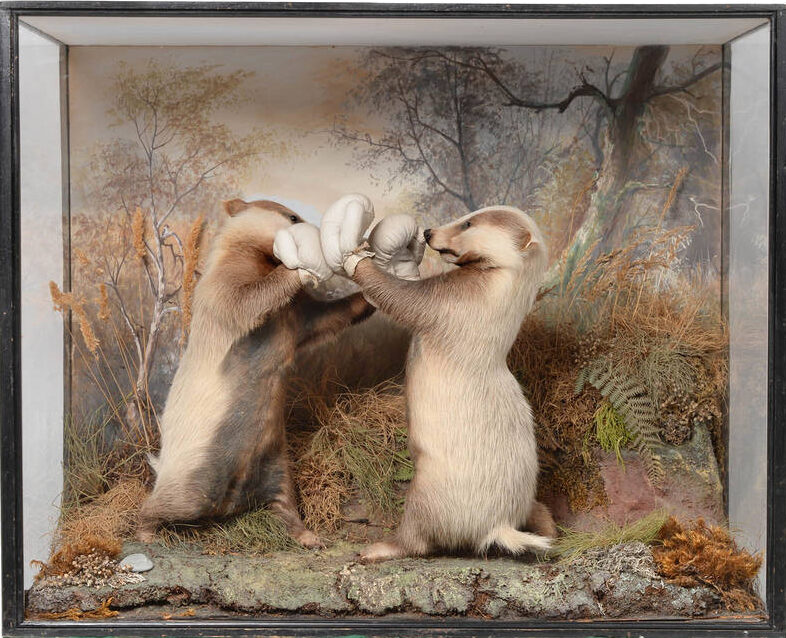

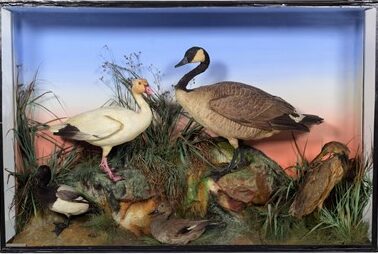

Edward Gerrard Senior, taxidermist, naturalist and osteologist, was at the epicentre of the golden age of natural history collecting and scientific discoveries that had started in the 1850’s but had exploded from the 1880’s, and taxidermy was the artistic and fashionable face of it. Taxidermy was a desirable and expensive and only the rich could afford to commission and display it in their drawing rooms. Museums were also commissioning examples of taxidermy species and supplying to museums became one of Gerrard’s specialities. Edward Gerrard Senior had an extensive network and knew the majority of the natural history dealers, and so introduced them to the British Museum and The Zoological Society and acted as a bridge between them for sales and made recommendations to the Museum about which specimens to buy.

For thirty-five years between 1870 – 1905 Edward Gerrard Junior, the son of Edward Gerrard Senior, was a natural history agent and taxidermist in his own right to the British Museum while running his own natural history business with his father. Amongst the specimens he presented or sold to the Museum during this time were many birds and mammals from exotic places including from Chile, Panama, Ecuador, Patagonia, Costa Rica, The Ural Mountains, Moscow, Queensland, Sardinia, Ceylon, New Guinea and Borneo. Many of these species were new or undiscovered and Edward Gerrard Junior was able to procure them and sell them to the Museum because he, like his father, had an extensive network and was at the centre of the world of dealers and collectors, and basically, he knew everyone there was to know.

Just one further example of this can be seen in the book published in 1905 by Henry Scherren entitled The Zoological Society of London : a sketch of its foundation and development, and the story of its farm, museum, gardens, menagerie and library” Edward Gerrard himself stated that the famous Tring quagga was purchased by him from a Mr. Franks of Amsterdam. Gerrard remounted the skin, which had been badly stuffed, and sold the specimen to the Hon. Walter Rothschild for his museum at Tring.

The firm of Edward Gerrard & Sons therefore had access to the best, the rarest, and the most interesting specimens both from collectors and from the Zoological Society and this advantage gave great energy to the establishment of their taxidermy and natural history business. Not only this, but the British Museum entrusted its most valuable commissions and its most important work to the Gerrards.

1850-1853

The Birth of the Family Business

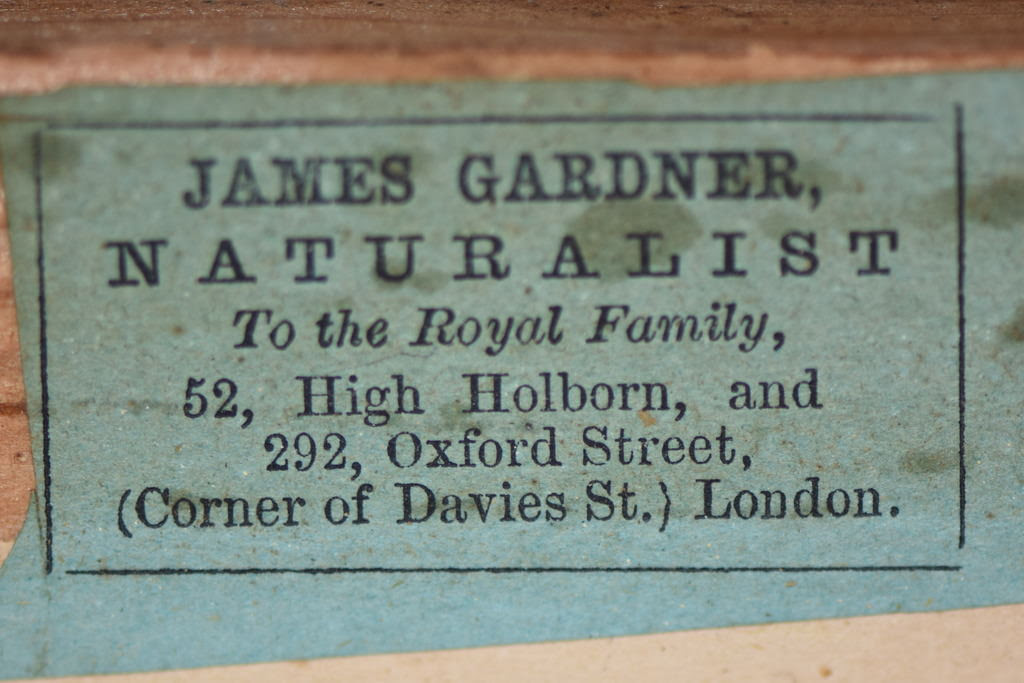

Edward Gerrard started his own business as a Taxidermist and Naturalist sometime around 1850, and possibly as late as 1853, while he was still employed at the British Museum.

Edward Gerrard was absent from the Great Exhibition of 1851. See the blog post about the taxidermy exhibitors at the Exhibition here

Edward Gerrard, who was to become one of the top three British taxidermy firms of the Victorian era, was absent from the list of exhibitors because it’s highly likely that he had not yet quite started his own business officially at that time in 1851. Taxidermy had previously been for science, and this had been the preoccupation of Gerrard. But now it was on the cusp of becoming an art.

I am surmising that Gerrard would have seen the sheer success of the exhibition and would have seen some of his contemporaries like Bartlett of Camden Town, and Hancock of Newcastle exhibiting there. I wonder if this influenced the timing of the launch of his own business outside his service at the British Museum under Dr. Gray? I’d say it is very likely that the Great Exhibition was the catalyst for Gerrard’s move to start his own business.

His son, Edward Junior, joined him in the business but it’s not proven exactly when. In those days it was normal for children to have to work, and education came second. In 1880 the Education Reform Act stipulated that children had to be educated up to the age of 10 years. Since Edward Junior was born in 1842 it is very possible that he did not have a long education.

In 1851 the census information records that Edward Gerrard Junior was age 8 and a scholar. Ten years later, in 1861 the census information records that Edward Gerrard Junior, at age 18, was already a naturalist. So, the assumption is that Edward Gerrard Junior could have joined his father in the business anytime from 1852 onwards, having had 10 years of education, and it is perhaps ok to assume that the date of 1853 could well have been the time that his son did join him in the business – at the tender age of just 11 years – and the date at which the business was really started having been fully motivated by the Great Exhibition in 1851.

It is worth reminding ourselves that both of his sisters – Sarah and Mary Ann Emma – were teachers, and continuing education at home would have been easy and very desirable.

The Gerrards can be categorised as the middle class of the time, since this class consisted of small manufacturers, shopkeepers, innkeepers, master tailors, clerks, teachers, lower ranks of professional people, railway and government officials and the like.

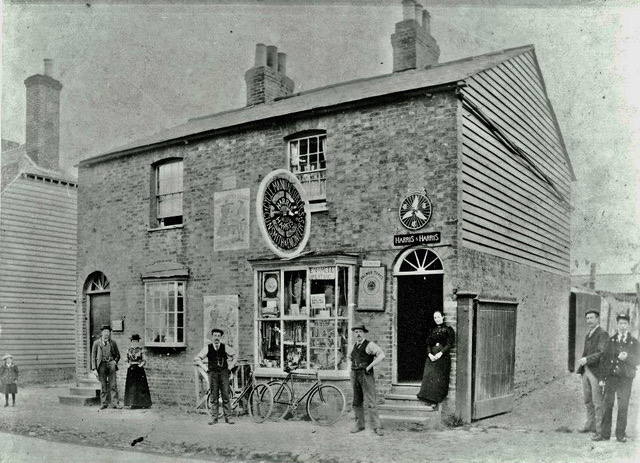

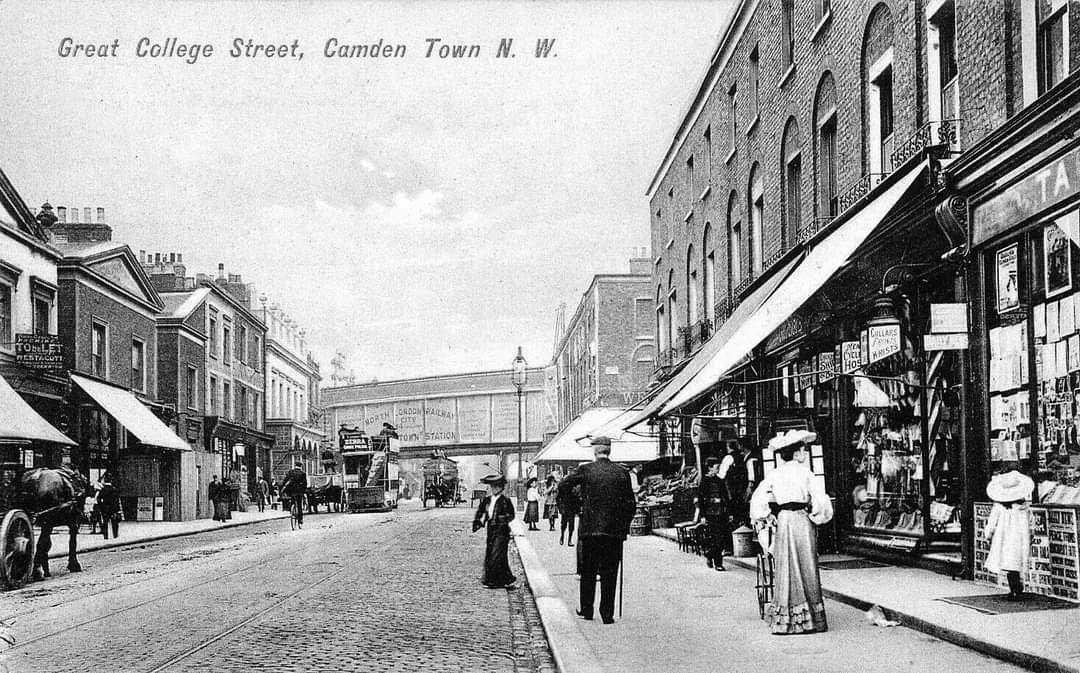

The photo below shows Great College Street in 1905

This street was a main thoroughfare, on the other side of the block that ran in parallel with College Place

College Place - where Edward Gerrard becomes the Establishment

From the 1860’s Mr Gerrard Senior and his son Edward Junior, ran the family taxidermy business in workshops known as “Camden Studios” behind 61 College Place.

Edward Gerrard Junior had become an established and well-respected taxidermist and naturalist aside his father and between 1870 – 1905 Edward Gerrard Junior in his own right was a natural history agent and taxidermist to the British Museum

The Gerrard family taxidermy business would continue to run at the Camden Studios at the back of 61 College Place (also called the Natural History Studios by Gerrard Junior) for nearly 100 years until the 1960’s. After this date the company’s Hire Division was established and ran until the early 1990’s.

At the start of their business, College Place was the pre-eminent and de-facto location for the Gerrards, since not only did they rent the workshops there from the 1860’s, but earlier from 1856 they had also moved to live at number 31 College Place and the census later places them living at number 61 College Place, immediately adjacent to the workshops, from 1891.

In parallel, Trade directories still show Gerrard Senior using 54 Queen Street as late as 1884 and it appears that Queen Street was always kept on and used as a contemporary meeting place for Edward Gerrard Senior.

In London in this period, people rented their homes as standard. A builder would build a row of homes, number them and then sell the houses to landlords, who in turn rented them out. A person might pay rent on the same house for 30 years. It was common practice to rent better places as your income rose. Despite numerous other published sources that seem to indicate that the location of Gerrard’s workshop changed several times during their history, in fact nothing could be further from the truth.

The company’s eventual relocation in the 1960s just before their business closed permanently was as a result of the expiration of a 99 year lease from “the church” (possibly the Wesleyan Baptist church which owned property in the nearby area) on their premises, at that time described as “61 College Place” but which in fact various sources confirm comprised the four buildings known as Camden Studios, with the possible later addition (either to the existing lease or by purchase of the freehold) of No 61 which was in front of Camden Studios and at the side of which was the access passage to the workshops.

This clearly shows that Gerrard occupied and used the Camden Studios site (behind 61 College Place) continuously from the early 1860s. The various ‘relocations’ alluded to in some accounts are misleading, but likely to relate to separate ‘front office’ operations, which makes sense given the often-unpleasant aspects of the Gerrard’s day to day business as well as the amount of space required to carry it out, in addition to storage requirements – neither of which could have been carried out at scale in a domestic residence.

RETIREMENT FROM THE BRITISH MUSEUM

Edward Gerrard Senior

Edward Gerrard Senior retired from his fifty-six-year tenure at the British Museum in 1896 and this was reported in the newspaper “The Morning Leader” on Saturday 19th September 1896. The newspaper cost one halfpenny.

The article reads: “Mr Edward Gerrard of the Zoological Department at the British Museum who is retiring after fifty-six years’ service was employed as a naturalist – ere he entered the service of the trustees – in the old museum of the Zoological Society, which stood on the site of the present Alhambra.

Mr Gerrard’s connection with the British Museum dates from the old Montagu House and Sir Henry Ellis’ days and he has watched the growth of the national collection of Mammalia from a few hundred specimens to its present proud pre-eminence. He is now eighty-six, and when in reminiscent mood will tell many good stories of the eminent zoologists and naturalists who have sought his assistance”.

DEATH OF EDWARD GERRARD SENIOR

PROBATE RECORD

There’s another post in this blog about the circumstances surrounding his death but when Edward Gerrard Senior died in 1910 the probate record shows that he left his son, Edward Junior, the sum of £548 12s. 6d. In today’s money this is the equivalent of about £60,000 taking average inflation into account. Note that also this money was left to his son, as per the traditions of the time, and not to his living daughter, Mary Ann Emma.

THE UNIVERSAL EXHIBITIONS

Riding the Wave of Success with 3 gold medals

The Great Exhibition (1851), the Colonial and Indian Exhibition (1886), and the Empire of India Exhibition (1895) were international in focus and form the beginning and peak of the British exhibition craze.

The peak of British taxidermy was from 1880 until 1914 and there were world and international Expos during this time that gave birth to the beginning of the taxidermy and natural history hey-day including Paris 1878, Sydney 1879, Melbourne 1880, Paris and Rouen 1881, Antwerp 1885

Gerrards were riding the cusp of the wave when they were present at some of these expos up until the first world war, and this period is historically considered the peak of their business. The Gerrard company attended and exhibited at:

1883: Calcutta – medal awarded

1886: Colonial and Indian exhibition of London – medal awarded

1887: International exhibition of Adelaide – medal awarded

1891: French exhibition of Moscow – medal awarded

1897: Intl expo in Brussels: Gold Medal awarded

1900: Universal Exhibition in Paris: Gold Medal awarded

1904: St Louis World Fair: Gold Medal awarded

1907: International exhibition in Dublin

1908: Franco-British exhibition of London

1910: Universal Exhibition in Brussels

1911: Imperial exhibition in London

1913: Universal Exhibition in Ghent

The End Of An Era And The beginning Of A New One

By the time the Edward Gerrard & Sons won its first gold medal at the International Expo in Brussels in 1897 Edward Senior had been retired for a year, and they had already been awarded medals at earlier exhibitions – Dublin, Calcutta, Moscow, Indian and Colonial and Adelaide, and so his son and grandsons amongst other employees of the firm will have been central to their presence here.

There were 27 participating countries at the Brussels Expo, and an estimated attendance of 7.8 million people.

Winning their first gold medal in Brussels must surely have been one of the highlights of Edward Gerrard Senior’s life, and before he died in 1910, he would see the company that he conceived and built go on to win another gold medal and a Diploma of Honour in Paris in 1900 (for their exhibit entitled “Ceylon Jungle”and a further gold medal for their exhibit “Big Game of Africa” at St. Louis in 1904.

I WONDER

I wonder what Edward Gerrard Senior would think now if he knew that even 130 years after he died, his company was still being talked about and researched? If he knew that his specimens were still collected and revered? If he knew that the fashion for taxidermy had waxed and waned but was now hunted by interior designers, museums and collectors alike?

But most of all, I wonder what he would think about our planet’s crisis and the urgency of the need for conservation of our natural world?