The Great Exhibition Works of Industries of All Nations 1851

At The Crystal Palace, Hyde Park, London

The Great Exhibition Works of Industries of All Nations 1851

The Great Exhibition 1851 sets a new scene in Britain where Art and Science plays its part

The Great Exhibition 1851.

Sets the scene for dramatic changes in the economy and social fabric of Britain. Art and Science plays its part.

The Great Exhibition 1851, housed within the ‘Crystal Palace’, embodied Prince Albert’s vision to display the wonders of industry from around the world and embodied the spirit of awakening of the Victorian era.

In France there had been national exhibitions since 1798 and the eleventh of these, The French Industrial Exposition of 1844 at the Champs-Élysées in Paris was the motivation for Prince Albert and Henry Cole, the organiser, to conceive The Great Exhibition in London.

The Great Exhibition 1851.

They pushed forward with it in the face of opposition from parliament, but eventually gained approval when they proposed that the event should be self-financing.

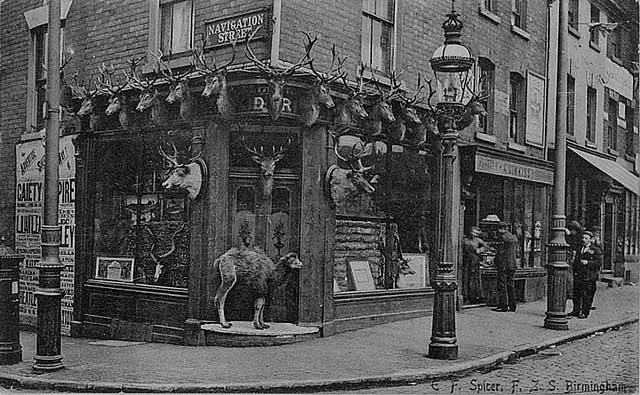

Joseph Paxton designed the Crystal Palace that would eventually house the exhibition in Hyde Park. His glass and iron conservatory that he had originally produced for the Duke of Devonshire’s Chatsworth House was used as the blueprint.

Visitors to The Great Exhibition 1851

Queen Victoria opened the Great Exhibition 1851 on 1 May, on schedule. She became a frequent visitor. At first the price of admission was £3 for gentlemen, £2 for ladies. They came in throngs, in their elegant carriages, leaving them at a separate entrance to be valet-parked. Saturday mornings were reserved for invalids. From 24th May the masses were let in for only a shilling a head. And they came in their thousands, factory workers sent by their employers, country villagers sent by benevolent landowners, strings of schoolchildren. The country men came wearing their best smocks, staring at all the Londoners and foreigners.

The travel agent Thomas Cook arranged special excursion trains. A third-class return ticket from York cost only five shillings. One old lady even walked, all the way from Penzance.

There was even a mysterious Chinese man in full mandarin robes, who stepped forward as the royal procession passed. He was treated, just in case he was important, as a visiting dignitary, but he turned out to be the captain of a Chinese junk moored in the river.

By the time the Exhibition closed, on 11 October, over six million people had gone through the turnstiles. Instead of the loss initially predicted, the Exhibition made a profit of £186,000, most of which was used to create the South Kensington museums. Those were Albert’s memorial. His Queen commissioned the statue of him, sitting under a gilt canopy opposite the Royal Albert Hall with a copy of the Exhibition catalogue on his knee.

A Showcase For Art, The British Empire, and Science

Although the original aim of this world fair that the Victorians named The Great Exhibition 1851 had been as a celebration of art in industry for the benefit of All Nations, in practice it appears to have been turned into more of a showcase for British manufacturing: more than half the 100,000 exhibits on display were from Britain or the British Empire.

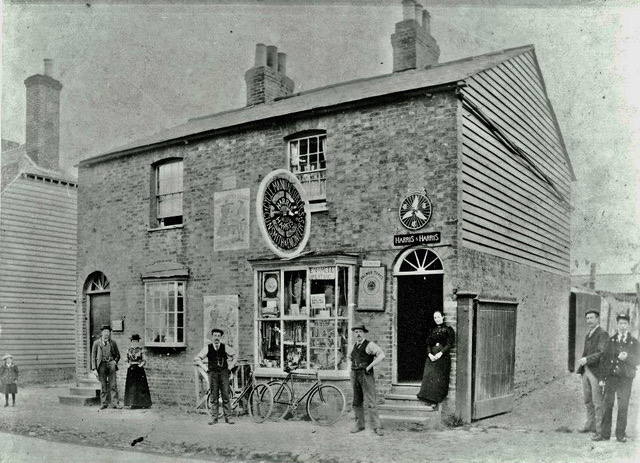

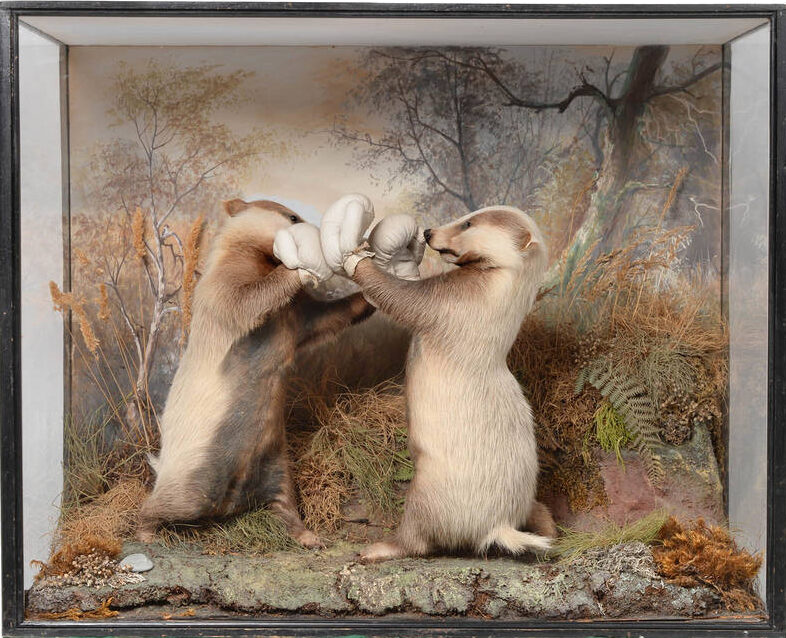

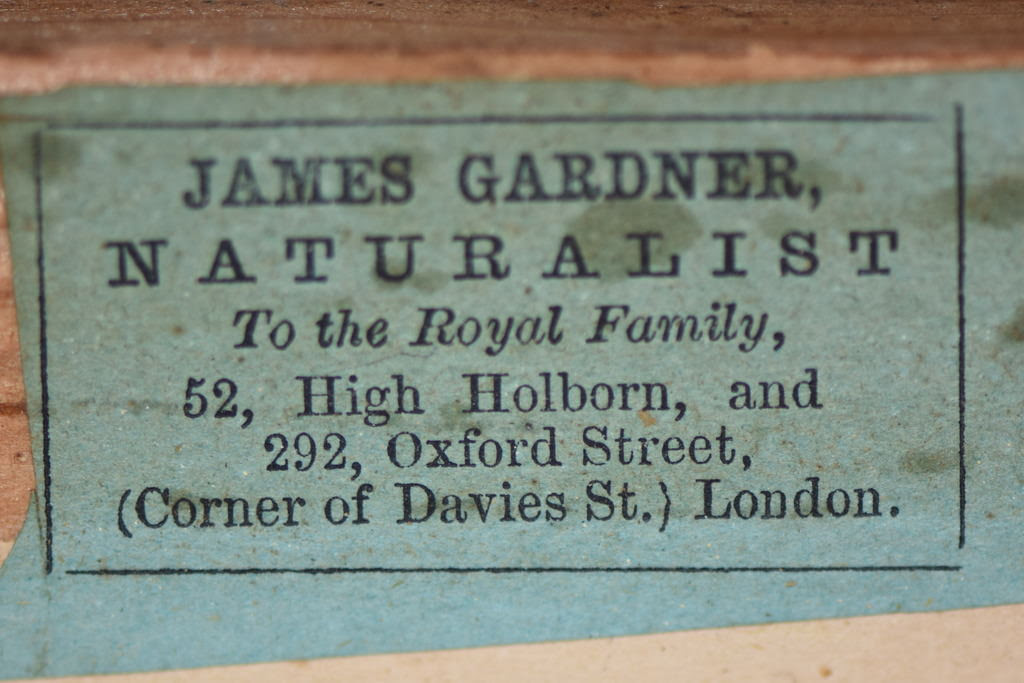

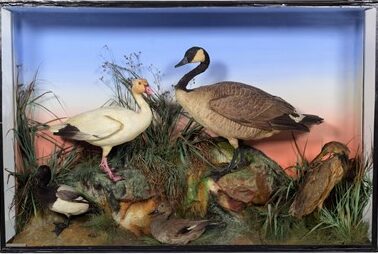

Britain’s explorers and scientists and new taxidermy artists were represented by the likes of John Hancock, James Gardner, William Bartlett, and John Leadbetter, while Edward Gerrard was still at the dawning of his business and was absent, and while John Gould saw a commercial opportunity and had set up a separate exhibition of hummingbirds at the ZSL which required a paid entry ticket. The taxidermy displays and reviews at The Great Exhibition 1851 are described in the next post.

The biggest of all was the massive hydraulic press that had lifted the metal tubes of a bridge at Bangor invented by Stevenson.

Next in size was a steam-hammer that could with equal accuracy forge the main bearing of a steamship or gently crack an egg.

There were adding machines which might put bank clerks out of a job; a ‘stiletto or defensive umbrella’– always useful – and a ‘sportsman’s knife’ with eighty blades from Sheffield – not really so useful.

One of the upstairs galleries was walled with stained glass through which the sun streamed in technicolour.

Almost as brilliantly coloured were carpets from Axminster and ribbons from Coventry.

There was a printing machine that could turn out 5,000 copies of the popular periodical the Illustrated London News in an hour, and another for printing and folding envelopes, a machine for making the new-fangled cigarettes, and an expanding hearse.

In short, as Queen Victoria put it in her Diary, ‘every conceivable invention’.

Canada sent a fire-engine with painted panels showing Canadian scenes, and a trophy of furs.