Taxidermy at The Great Exhibition 1851

Fantastic Beasts

Taxidermy At The Great Exhibition 1851

Taxidermy At The Great Exhibition 1851

Much has been written about how the grand amphitheatre of glass gloried in a manufactured culture of progress. The Crystal Palace served as the nation’s living room.

Taxidermy had been on show before (for instance in small museums and freak exhibits), but never had the British public been treated to such a variety of reanimated animals under one roof. Nor had stuffed critters been given such patriotic, scientific and decorative kudos.

To the Morning Chronicle, this augured the moment when taxidermy—as art and a science— became “respectable and interesting” (Morning Chronicle, 1851a).

This ratification was important, not least because of the way in which spectatorship segued seamlessly into home consumption. As Thomas Richards has noted, the Great Exhibition represented both “museum and a market” (1990: 19) and one in which product,national pride and spectacle were conjoined to invite a migration of goods from public to private spaces. Sometimes, the connection between looking and buying was direct—such as the furriers who advertised their sartorial wares with full-size specimens of the animals from which they derived.

Quoted from Karen R. Jones under the creative commons license in her paper published 2021 entitled “Fantastic Beasts in the Great Indoors: Taxidermy, Animal Capital and the Domestic Interior in Britain 1851-1921”

Queen Victoria, reputedly, was so impressed with the charismatic beasts on the Nicholay of Oxford Street stand that she ordered fur-coats for her and Albert.

At other times, meanwhile, the process was more abstract, the public installation of taxidermy as a scientific and decorative adornment translating into a cultural sensibility that dictated what looked good and, crucially, what had meaning in the private household.

If visitors needed a prompt, of course, they could consult the souvenir catalogues and commemorative booklets that provided a useful inventory of the products on display.

Taxidermy and Natural History Displays at the Great Exhibition 1851

Early pioneers display their craft

Taxidermy At The Great Exhibition 1851

The taxidermists and natural history displays signalled the beginnings of the new opportunities in Britain to develop the commercial aspect of the art of taxidermy.

So far, taxidermy had served science and had been criticised as being “wooden” and less than life-like, but 1851 was a turning point because from here on Taxidermy adopted an aesthetic perspective – it was now on the cusp of being made for pleasure, décor and art.

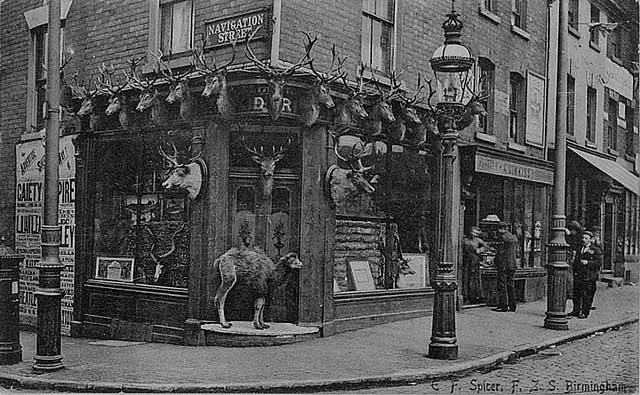

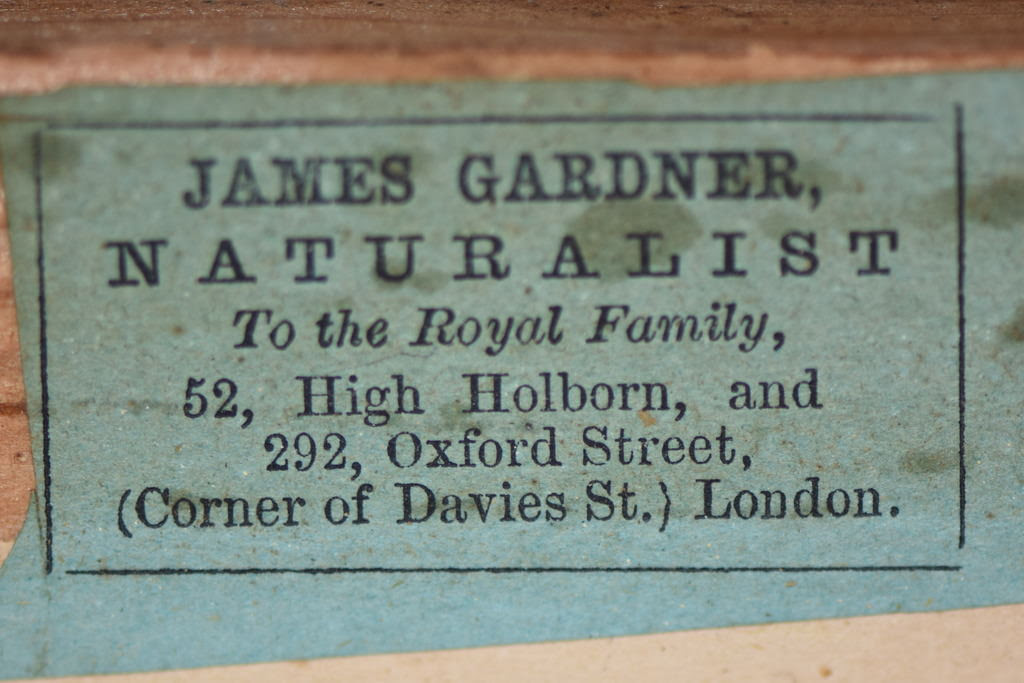

The twenty-six taxidermy exhibitors, thirteen of which came from Britain, were the early pioneers in the taxidermy world and were placed in the Fine Art Court at the Great Exhibition of 1851 under class number XX1X, sub category J and included the firms of James Gardner of Oxford Street, John Hancock of Newcastle, Bartlett of Camden Town, and John Leadbeater of Brewer Street,

The catalogue of all exhibitors that includes taxidermy and natural history displays is found in volume 2 of the catalogue on pages 444-450 under the miscellaneous and small wares section and shows the range of animal products on display from several countries.

This catalogue can be reviewed and downloaded under a creative commons license online

British Taxidermists At The Great Exhibition 1851

There were 13 British Taxidermists displaying their craft at the Great Exhibition of 1851.

James Gardner, Oxford Street, London:

foreign birds, including hummingbirds, and birds of prey

Abraham Bartlett, Camden Town, London:

multiple displays including a lifesize model of the extinct Dodo

John Hancock of Newcastle:

displays of birds and mammals

John Leadbetter, Brewer Street, London:

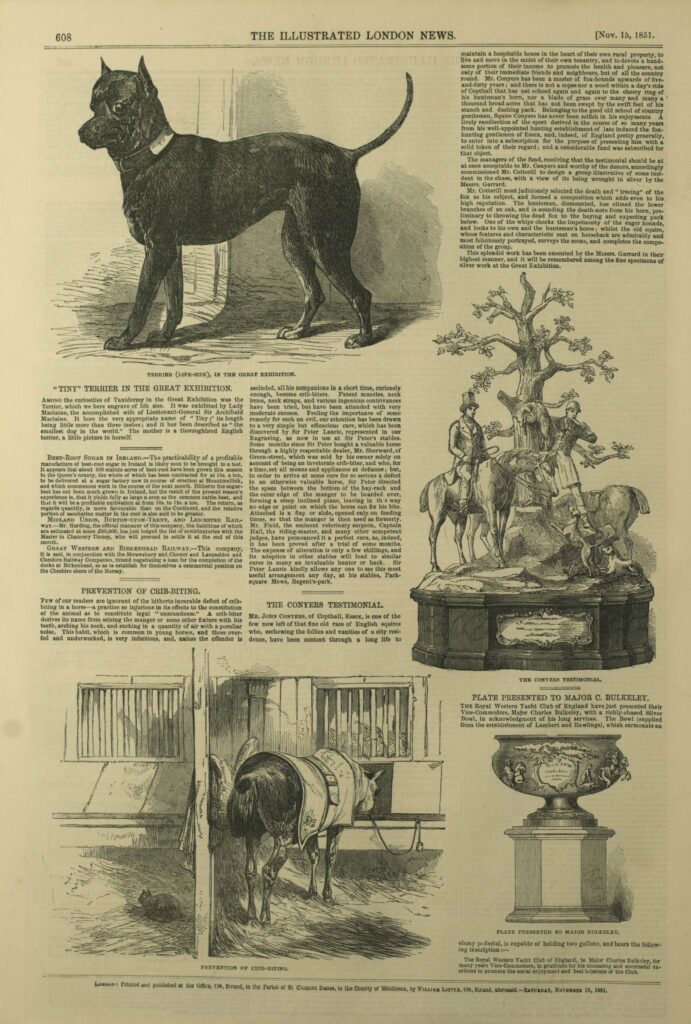

A miniature Terrier dog, domes with birds, Indian Rollers

William Dunbar of Scotland:

Displays of birds

Reverend James B.P. Dennis of Bury St. Edmunds:

A Peahen and a Gull

Thomas Harbour of Reading:

Display of birds

Spencer of London:

Birds set on a display of artificial water

Withers of Devizes:

A case of Partridge

Williams of Oxford Street, London:

A display of birds

Walford of Essex:

Various species of birds

C. Gordon of Dover:

A display of small birds

To today’s enthusiasts and collectors who look back at history, there appear to have been at least three notable absences:

John Gould | Edward Gerrard | Charles Waterton

John Gould played a clever game to make money from his absence.

Edward Gerrard’s commercial business was only just beginning.

Charles Waterton went off in a huff and refused to be present.

The stories of these, we shall read further….

And there was one huge non-British sensation.

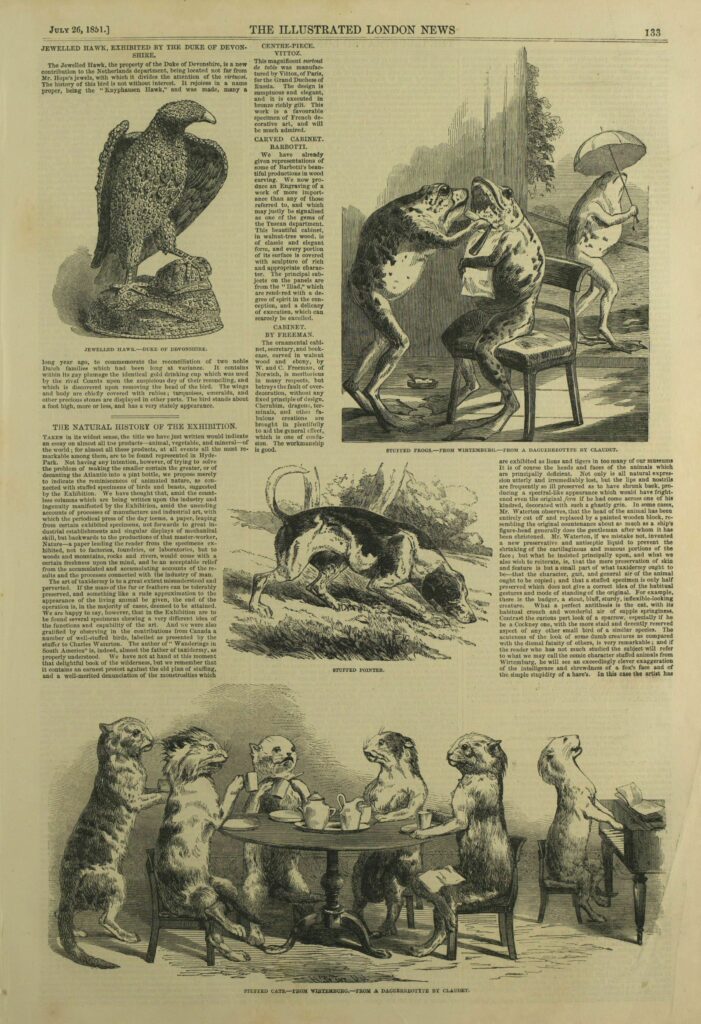

Hermann Ploucquet stole the show with his tableaux. More about this down the page.

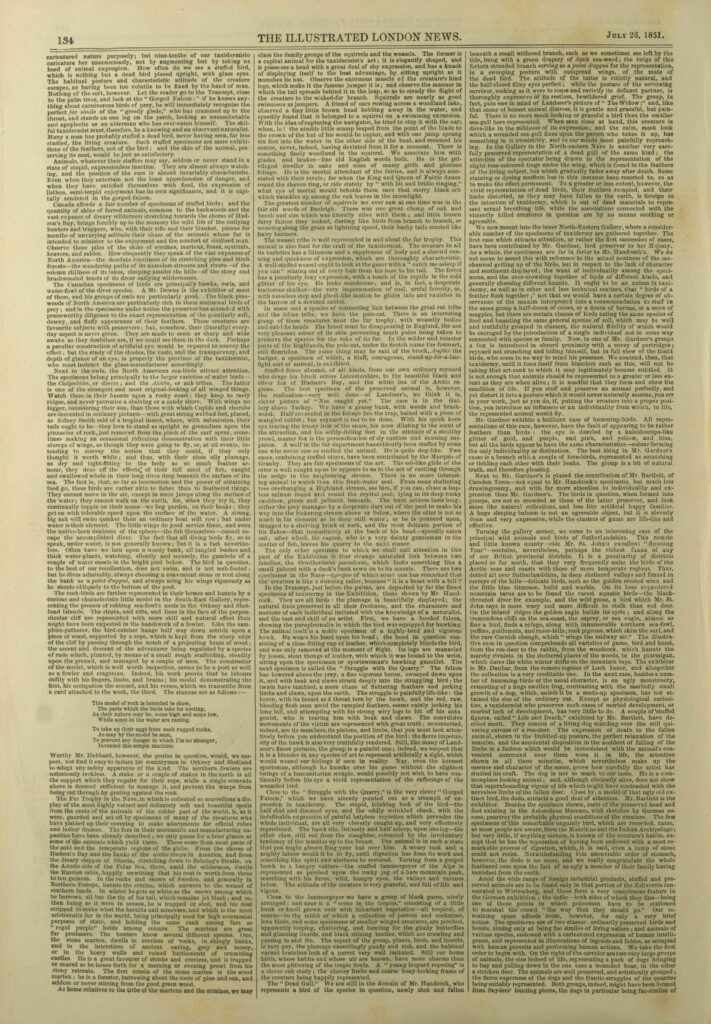

Illustrated London News Review of the Taxidermy Displays at The Great Exhibition 1851

On 26 July 1851 appeared a review of these taxidermy displays at the Great Exhibition. From this, we get a good picture of what was on display, by whom, and the general consensus on its appeal. Some exhibitors fared better than others!

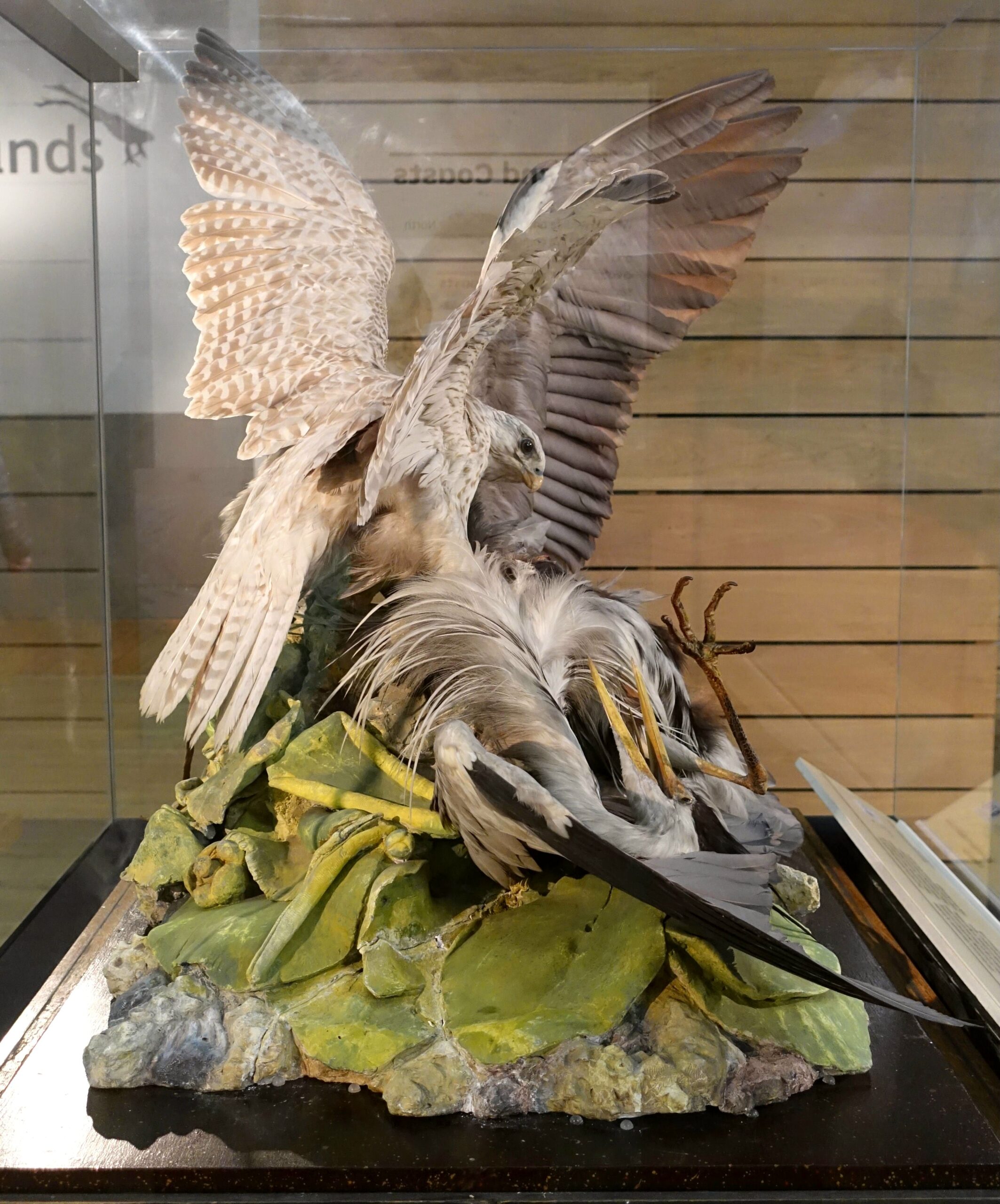

Illustrated London News Review of John Hancock's display at the Great Exhibition 1851

John Hancock (1808-1890) of Newcastle became one of the leading taxidermists of his day. He specialised in supplying wealthy gentlemen collectors and he was also a keeper of falcons, so his experiences informed his taxidermy displays very well, and his natural and very accurate representations, particularly of birds of prey in their natural habitats, earned him a Prize Medal at the exhibition and a glowing review.

The reviewer writes:

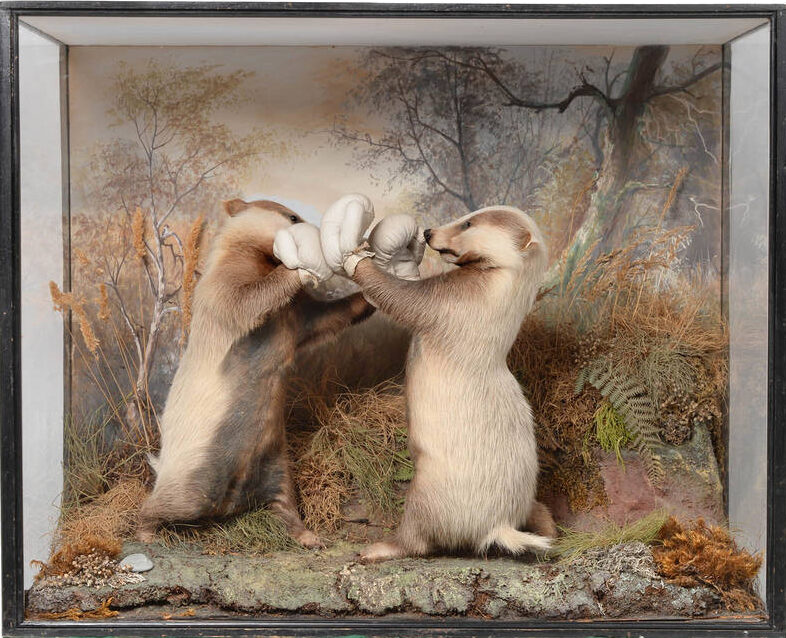

“In the transept, just before the palms, are deposited by far the finest specimens of Taxidermy in the Exhibition, those shown by Mr Hancock. They are all birds: the plumage is beautifully displayed, their natural tints preserved in all their freshness and the characters and motions of each individual with the knowledge of a naturalist, and the tact and skill of an artist.

First, we have a hooded falcon showing the paraphernalia in which the bird was equipped for hawking……….The next specimen is called “Struggle with the Quarry”. The Falcon has towered above the prey, a fine vigorous heron, swooped down upon it, and with beak and claws struck deeply into the struggling bird; the twain have tumbled, a mere chaos of fluttering feathers, and jerking limbs and claws above the earth……The convulsive movements of the victim are conveyed with great truth”

The reviewer goes on to praise Hancock’s display named “The Gorged Falcon” which is described as “very clever” and “a triumph of expression in Taxidermy”.

The Struggle with the Quarry that shows a Gyr Falcon attacking a Heron created by John Hancock for the Great Exhibition 1851 is in the Hancock Museum in Newcastle

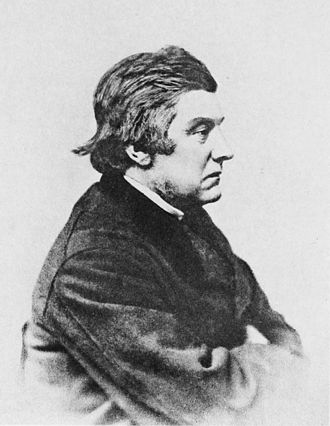

Photograph of John Hancock

Artists painting of John Hancock

Illustrated London News Review of James Gardner’s display at the Great Exhibition 1851

Illustrated London News Review of James Gardner’s display

James Gardner Senior exhibited in class XX1X (29) sub-category J and was exhibitor number 223. The Gardner display included “various specimens of stuffed birds; one half being birds of prey, indigenous to Britain, and the other showy-plumaged birds”.

Sadly, the review of his work was not glowing, and in terms of comparison to Hancock and Bartlett, the review was not too favourable, and the appraisal of his work came off worst in the group being “far inferior” to that of Hancock’s. James Gardner Senior’s style at this point in the firm’s development was described in the same review as being “drawingroomy” and with the exception of two love-birds on a branch, the poses and settings of the mixed birds and mammals in his displays were described as having not enough individuality and expression, unlike Hancock’s.

The review includes statements such as “As a whole, the specimens are far inferior to Mr Hancock’s………..in respect to the lack of character and sentiment displayed”. He goes on to say, “now in one of Mr Gardner’s groups, a fox is introduced in absurd proximity of a covey of partridges, reynard not crouching and hiding himself, but in full view of the timid birds, who seem in no way to mind his presence”.

Mr Gardner is almost, but not quite, redeemed in the eyes of the review as he states “Mr Gardner exhibits a brilliant case of humming-birds. All……..have the fault of appearing to be rather feathers than birds”.

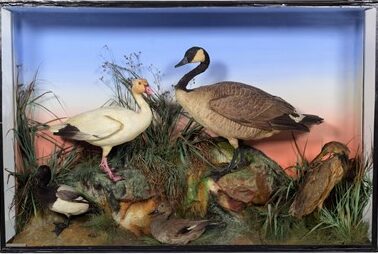

Illustrated London News Review of Abraham Bartlett's display at The Great Exhibition 1851

Abraham Dee Bartlett of Camden Town

Abraham Dee Bartlett born 27th October 1812 was one of the most prolific and important taxidermists of his time.

In the Great Exhibition of 1851 he was awarded the first prize for specimens of taxidermy which included, Eagle under glass shade, diver under glass shade (the property of her Majesty the Queen), snowy owl, Mandarin duck, Japanese teal, pair of Impeyan pheasants, sleeping Orang-Utang, Sun Bittern, Musk Deer, Cockatoo, Foxes; Carved Giraffe; two bronze medals from the Zoological Society; Dog and Deer; Crowned Pigeons; Leopard and Wolf and prize medal for a model of the Dodo.

Illustrated London News review

“Next to Mr Gardner’s is placed the contribution of Mr. Bartlett of Camden Town – not equal to Mr Hancock’s specimens, but much less “drawingroomy”, and with far more attention to individuality and expression than Mr. Gardner’s. The birds in question when formed into groups are not so crowded as those of the latter preserver and look more like natural collections and less like artificial happy families. A huge sleeping baboon is not an agreeable object, but it is cleverly done and very expressive while the clusters of game are lifelike and effective”.

Bartlett also displayed a recreated model of the Dodo, which the reviewer mentions.

He says “….the dodo is no more, and we congratulate the whole feathered race upon the fact of so ugly a member of their family having vanished from the earth”.

Was The Great Exhibition of 1851 the catalyst for Edward Gerrard's business?

Edward Gerrard, who was to become one of the top three British taxidermy firms of the Victorian era, was absent from the list of exhibitors because it’s highly likely that he had not yet quite started his own business officially at that time. Taxidermy had previously been for science, and this had been the preoccupation of Gerrard. But now it was on the cusp of becoming an art.

I am surmising that Gerrard would have seen the sheer success of the exhibition and would have seen some of his contemporaries like Bartlett of Camden Town, and Hancock of Newcastle exhibiting there. I wonder if this influenced the timing of the launch of his own business outside his service at the British Museum under Dr. Gray? I’d say it is very likely that the Great Exhibition was the catalyst for Gerrard’s move.

Gerrard and his contemporary, the prize-winning exhibitor Bartlett, had many similarities in their experiences and profiles. Abraham Bartlett ran his business from 1846 from a large house in Great College Street, Camden Town. This was very near to Gerrard’s own business in College Place (from circa 1860). Bartlett, like Gerrard, also worked with Dr. J. E. Gray of the British Museum, and he knew all the movers and shakers of the day like Gerrard did, including Gould, Blyth, and Sir Joseph Paxton the designer of the Crystal Palace, and he corresponded regularly with Charles Darwin as did Bartlett.

Surely Gerrard was spurred on, not to be outdone?

Surely, Gerrard could not have accepted his contemporaries’ success at the 1851 Exhibition without being sure he could do just as well?

One of the similarities that neither of them would be happy to know is that they are both now buried in their respective family graves at Highgate Cemetery, Mr Bartlett having died in 1897 and Mr Gerrard having died in 1910.

John Gould was absent in the Taxidermy Class at the Great Exhibition of 1851 but it was deliberate!

John Gould was an ornithological artist and is widely known for his hand drawn paintings in two high profile books – Birds of Europe and Birds of Great Britain. He worked with two other artists to create these books – Edward Lear and his wife, Elizabeth Gould. He was also a taxidermist.

He did not exhibit at the Great Exhibition – he had another idea that would make him some money. In parallel with the timing of the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park which had free entry, he staged his own exhibition at the Royal Zoological Society, just three miles away from Hyde Park. He wagered that all the visitors to London would be motivated by the displays at The Crystal Palace in Hyde Park and they would want to come and see his display of taxidermy hummingbirds that he staged in a self-financed wooden building at the ZSL, and that they would pay for it. He was right. He charged visitors 6d and is said to have made a profit of eight hundred pounds.

75,000 people visited Gould’s display of Hummingbirds in 1851 compared with over six million people who visited the Crystal Palace. The majority of his hummingbird collection was later sold to the British Museum.

The absolutely amazing fact about Gould is that, at this point in time, he had not ever seen hummingbirds alive, and would not see them alive until he made a visit to the USA 6 years later in 1857.

India's display at The Great Exhibition 1851

India contributed an elaborate throne of carved ivory, a coat embroidered with pearls, emeralds and rubies, and a magnificent howdah and trappings for a rajah’s elephant. A large horse-drawn van brought her from Essex to Hyde Park.

The Elephant did not come from India at all. The Saffron Walden Museum had bought her skin from a contact in South Africa in the 1830s and she had been on display in the museum for two decades. She was also, as an African elephant, the wrong species. Nobody seemed to mind that this African skin was found in Essex and exhibited in London as an Indian animal.