OBITUARY OF EDWARD GERRARD: b. October 1810 d. 19th June 1910

Transcript: St Pancras Herald 24 June 1910

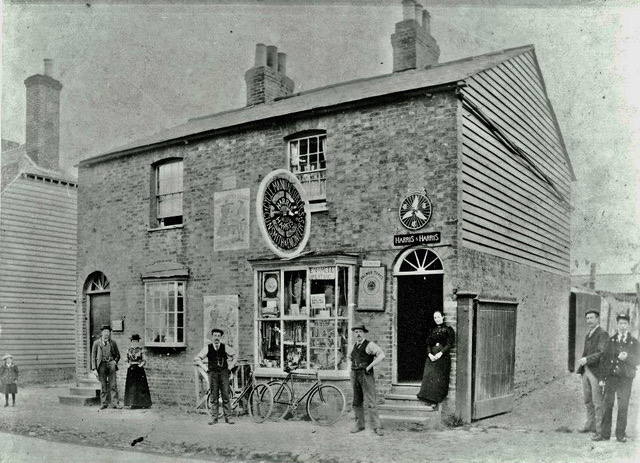

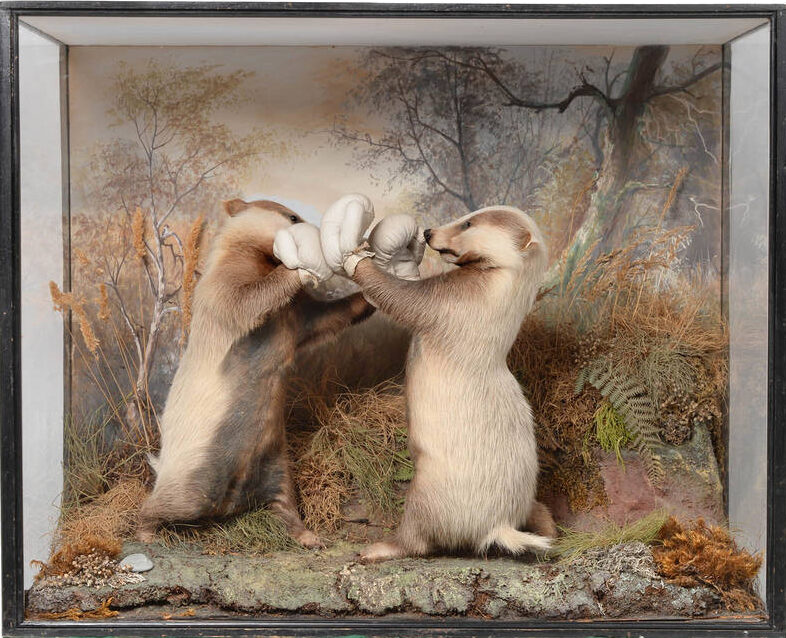

Wanting but four months to attain the distinction of becoming a centenarian, there passed away on Sunday at his residence, 61 College Place, Camden Town, one of the oldest and almost a life-long residents, of St. Pancras, in the person of Mr Edward Gerrard, the well-known naturalist and taxidermist whose association with that profession made him one of the most interesting personalities of our town and time.

The late Mr Gerrard, whose health was remarkably robust, enabling him to continue his daily walks abroad until his 95th year, had actually attained the great age of 99 years and 8 months, having been born in Oxford in 1810, whence he came with his parents very soon after his birth to Marylebone and shortly afterwards moving into to St Pancras, where he filled the remainder of his useful and industrious years, surviving his wife some 62 years, and now leaving two surviving children Mr Edward Gerrard and Mrs Payne, six grandsons and six granddaughters and ten great-grandchildren. One daughter, Miss Gerrard, who predeceased her father, was a much-esteemed headmistress at the Medborn Street Higher-Grade Board school – now the Stanley (Medburn) LCC School – where her sister, Mrs Payne, is now mistress and where both the late Miss Gerrard and the present Mrs Payne are held in the highest affection by wide circles of past and present girl pupils.

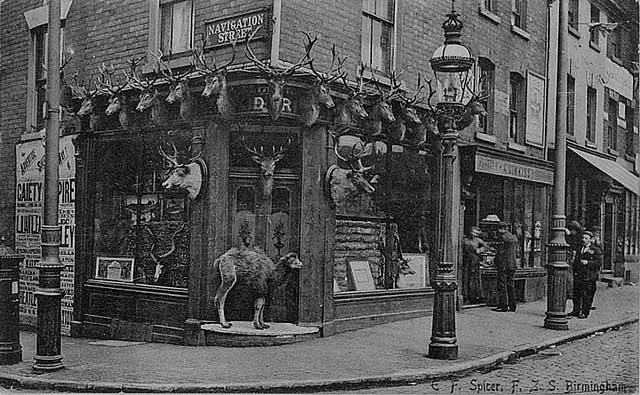

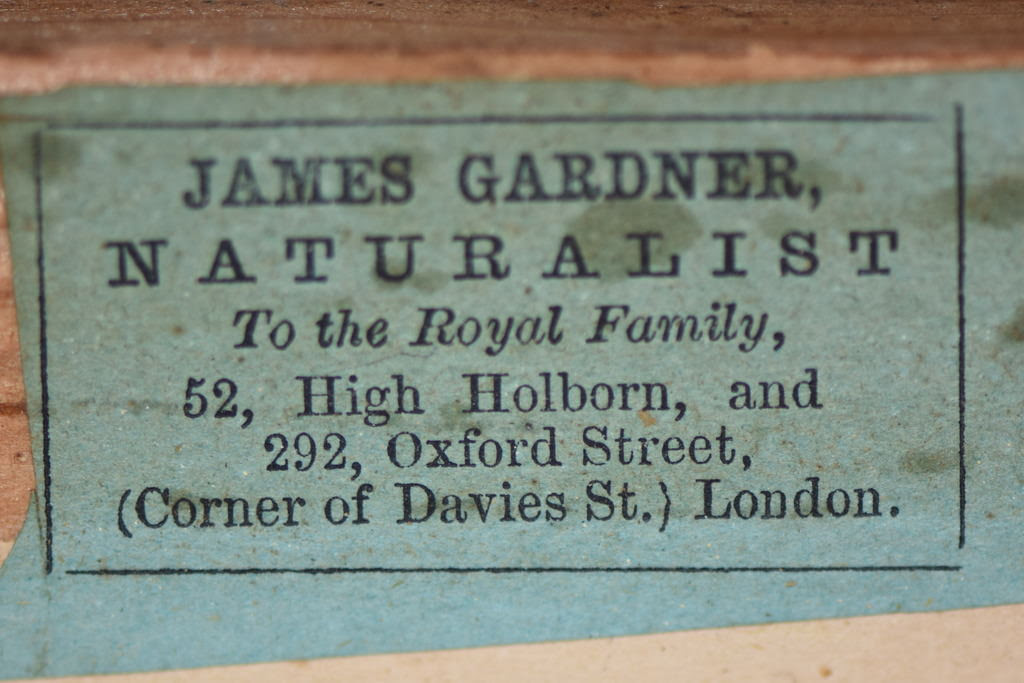

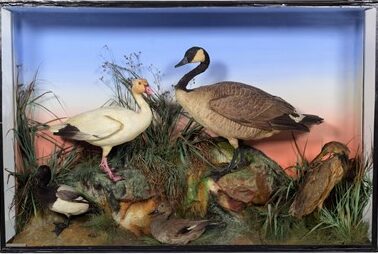

The late Mr Gerrard entered the service of the Zoological Society in its early days in Bruton Street, where the Alhambra now stands and after ten years with the Society he joined the Zoological Department of the British Museum, and with Dr. Gray, superintended the transfer of the Zoological collection from Great Russell street to South Kensington, and assisted in arranging the specimens in the now museum. Here, he served under Dr. Gray, Sir Richard Owen, Dr. Gunther and Sir William Flower, and well-remembered seeing the late King when Prince of Wales run unattended up the stairs from his carriage into the museum to attend the Trustees meeting. His service extended over fifty-six years and he retired in 1896 at the age of eighty-six.

He had lived under six sovereigns and had all the prominent zoologists of Great Britain and many of those of the continent of America, many of whom sought his assistance in their research, and of whom he would tell many good stories.

For the last fifty-four years he had resided at 61 College Place, having lived at Robert Street, Hampstead Road, for fifteen years previously, when Rhoden’s Dairy

His memory was excellent and could recite many portions of Shakespeare to the day of his death and would also recall several political verses and songs reminiscent of the days of the Corn Law League, of which he was a member. He was a great admirer of Daniel O’Connell, Bright and Cobden, whose meetings he always attended, and was one of the subscribers to the Cobden statue at the foot of High Street, Camden Town, as well as having been one of the special constables sworn in for the Corn Law riots. He remembered the trouble over the burial of Queen Charlotte, when the people dug a trench across Euston Road, then called The New Road, to defy the King, who had decided that the funeral should not pass through the City. He also would talk of the soldiers riding to Cumberland Market to arrest some of the Chartist rioters who were in hiding in some of the stables there. As a boy, he had climbed the railings which guarded Regent’s Park (then, a private Royal Park), and chasing the rabbits and birds which abounded there. He saw the first steamboat on the Thames, with its paddle-wheel at the stern, and also the first train run to Euston in 1837, the Link Boys, the “Charlies” (the predecessors of the present day policemen, on whom the young men of the day were very fond of burning his hut or watch box, if one should be found sleeping, and who would cry the hours through the night as they went along their rounds). He remembered the old woman at the Black Cap, Camden Town, the burning of the Houses of Parliament, at which he was present and being held up by his mother to see the soldiers returning after the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. Living so close to the spot he saw the mushroom beds and kitchen gardens of Camden street, and King street give place to houses, schools and public baths, and the little Inns of upper college place, and the larger one at the corner of King street with its three horse chestnut trees and horse trough, and outside seats and tables, first new-fronted and finally give way to the blocks of flats at present standing there. The subject of this biography came from a sturdy Wiltshire family and often spoke of a cousin Henry, a very strong man, killing a bullock with a branch because the animal attacked and killed his dog. This same cousin was called to the aid of a widow innkeeper who, having four soldiers billeted on her, was suffering insults at their hands, and it is related that these soldiers he threw out of the window one by one.

Mr Gerrard was almost a most active and abstemious man, walking across Hyde Park to and from the Museum daily, and since his retirement he took daily walks over Hampstead Heath and Highgate until, as stated above, at the age of ninety-five when motor-cars, cyclists and the like made the roads too dangerous for a man of his age.

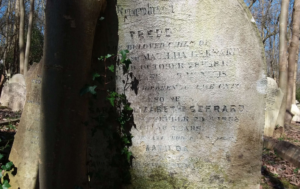

The internment took place yesterday (Thursday) in the family grave at Highgate Cemetery, the mourners being Mr Edward Gerrard, son; Mrs Payne, daughter; Mrs E.M. Gerrard and Mrs. H Gerrard, granddaughters in law; Mr Thomas Gerrard, grandson and Mrs T Gerrard; Miss Moore, cousin; Miss Payne, granddaughter; Mr and Mrs Mizens, and Mssrs A Boulenger, F.R.S, A Smith Z.F.S and Dr A Gunther F.R.S. heads of departments and other gentlemen from the Natural History Museum. The polished coffin with its heavy brass mountings, was borne to the last resting place on an open car, followed by three mourning carriages and quite hidden by the numerous and beautiful floral tributes from Mrs E Gerrard and Mrs Payne, Mr and Mrs T Gerrard, Mr and Mrs Baylis, Mr and Mrs Green, Mr and Mrs H Gerrard, Mr and Mrs Williams, Mr A.E. and G and Miss Payne, Mrs E.M. Gerrard and children, Mrs Baylis’ children, staff of E. Gerrard & Sons, staff of Natural History Museum, The Stanley School, Mr and Mrs Watson, Mrs and Mrs Easudier (?), Mr and Mrs Mizon (or Nixon?), Mr and Mrs Neilson, Miss Patsy More, Miss R. Moore, Mssrs Cole, Mssr Hardwick.

Mr G. Chatworthy, 92 High Street, Camden Town carried out the funeral arrangements.

Source: As printed in The St Pancras Herald, Friday June 24th 1910

IN THE FAMILY GRAVESTONE AT HIGHGATE CEMETERY ARE BURIED:

Edward Gerrard Senior 1910 age 99

Edward Moore Gerrard 1906 age 36, son of Edward Gerrard Junior, grandson of Edward Gerrard Senior

Francis T Gerrard 1902 Age 23, son of Edward Gerrard Junior, grandson of Edward Gerrard Senior

Matilda Gerrard 1899 Age 49, wife of Edward Gerrard Junior

Sarah E Gerrard 1898 Age 58, sister of Edward Gerrard Senior

Frederick Gerrard 1879, Age 3, son of Edward Gerrard Junior, grandson of Edward Gerrard Senior

PLAN OF THE FAMILY GRAVE SITE AT HIGHGATE CEMETERY

Source: Burial Ground Management System: https://highgate.burialgrounds.co.uk

The Victorian health situation

Perhaps one can imagine the circumstances in which two of Edward Gerrard Junior’s children and his wife died at what appear to be very young ages.

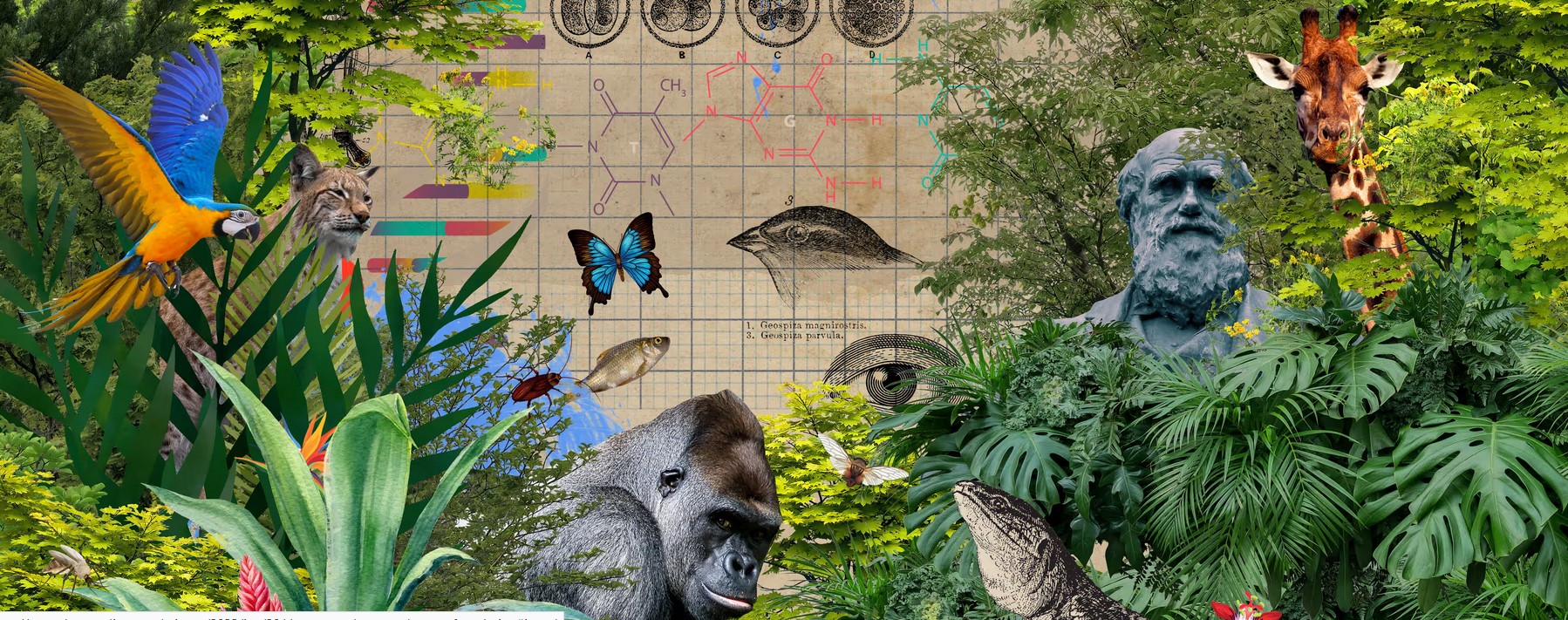

The Victorian period was a time of extraordinary change. Key scientific discoveries, changes in understanding about the human body and reform of housing, health and education transformed people’s lives and greatly improved life expectancy.

In the 1830s and 1840s epidemics of cholera, typhoid and influenza killed people in their thousands; surgeons amputated limbs in dirty, badly-lit rooms with no anaesthetic; and many ordinary people lived in cramped conditions with no running water. In the third quarter of the century the main causes of death included:

Smallpox, measles, scarlet fever, diphtheria, whooping cough, typhus, enteric fever,

simple continual fever, puerperal fever, diarrhoea and dysentery, cholera, and respiratory diseases.

By the end of the 1800’s, the link between poor health and living cramped together in back-to-back slums had been proven, Joseph Bazalgette had built sewers under London, Louis Pasteur had made the crucial discovery of germs and their link to disease, surgery was performed using both antiseptic and anaesthetic, and nursing reformers like Florence Nightingale had transformed hospitals from ‘gateways of death’ to clean, efficient places of healing.

It was also a time of great social change, particularly for women and children. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson became the first woman to practice medicine in Britain, and Millicent Fawcett led the campaign for votes for women. All children had access to education and became better protected from exploitation as miners, factory workers and chimney sweeps.

Sources: National Portrait Gallery and UK Dataservice.ac.uk

**