THE ZSL's

MENAGERIE IN REGENTS PARK FROM 1828

The birth of the Zoological Society of London (ZSL)

The birth of The ZSL & The Menagerie at Regent’s Park, its importance in the development of scientific knowledge of animals.

The Zoological Society of London known as The ZSL has been in existence since 1826, and the ZSL & The Menagerie at Regent’s Park and zoo since 1828, for almost 200 years and there are anniversary plans for 2026. The ZSL operates two zoos one in London and the other at Whipsnade, now a conservation zoo. For the whole of the 19th century the ZSL referred to the zoo as “The Menagerie”.

It is impossible to separate the birth of menageries and zoos in Britain from the creation and expansion of the British Empire.

By the end of the 19th century, Britain’s existing empire had expanded beyond recognition, and colonisation had become a moral mission to share and spread British values across the globe. This is an important aspect of the development of The ZSL & The Menagerie at Regent’s Park.

By the turn of the 20th century, the British flag had been raised right across the world map: from the farthest reaches of North America, across the Caribbean, over large swathes of Africa, throughout the Indian subcontinent and as far distant as Australia and New Zealand.

The cliché was that Britain’s influence, power and control was so far-reaching, so all-encompassing, that the Sun never set on its empire. And it was true.

THE ZSL WAS NOT THE FIRST ZOO IN BRITAIN

Although The ZSL & The Menagerie at Regent’s Park is probably the best-known zoo it wasn’t the first in Britain, since Henry I created what was effectively England’s first zoo in 1110, when he had a wall built to enclose his collection of animals at Woodstock, Oxfordshire. Among the animals on display were lions, tigers, porcupines, and camels.

A century later, it was moved to the Tower of London where it remained for 600 years.

The Tower menagerie developed into a popular attraction, and those who couldn’t afford the price were let in for free if they brought along a dog or cat to throw to the lions. Yes, really….

In 1832, after a string of incidents where the animals escaped and attacked each other, visitors and staff, the Duke of Wellington – Constable of the Tower – ordered the animals to be moved from the Tower Menagerie to their current home in Regent’s Park.

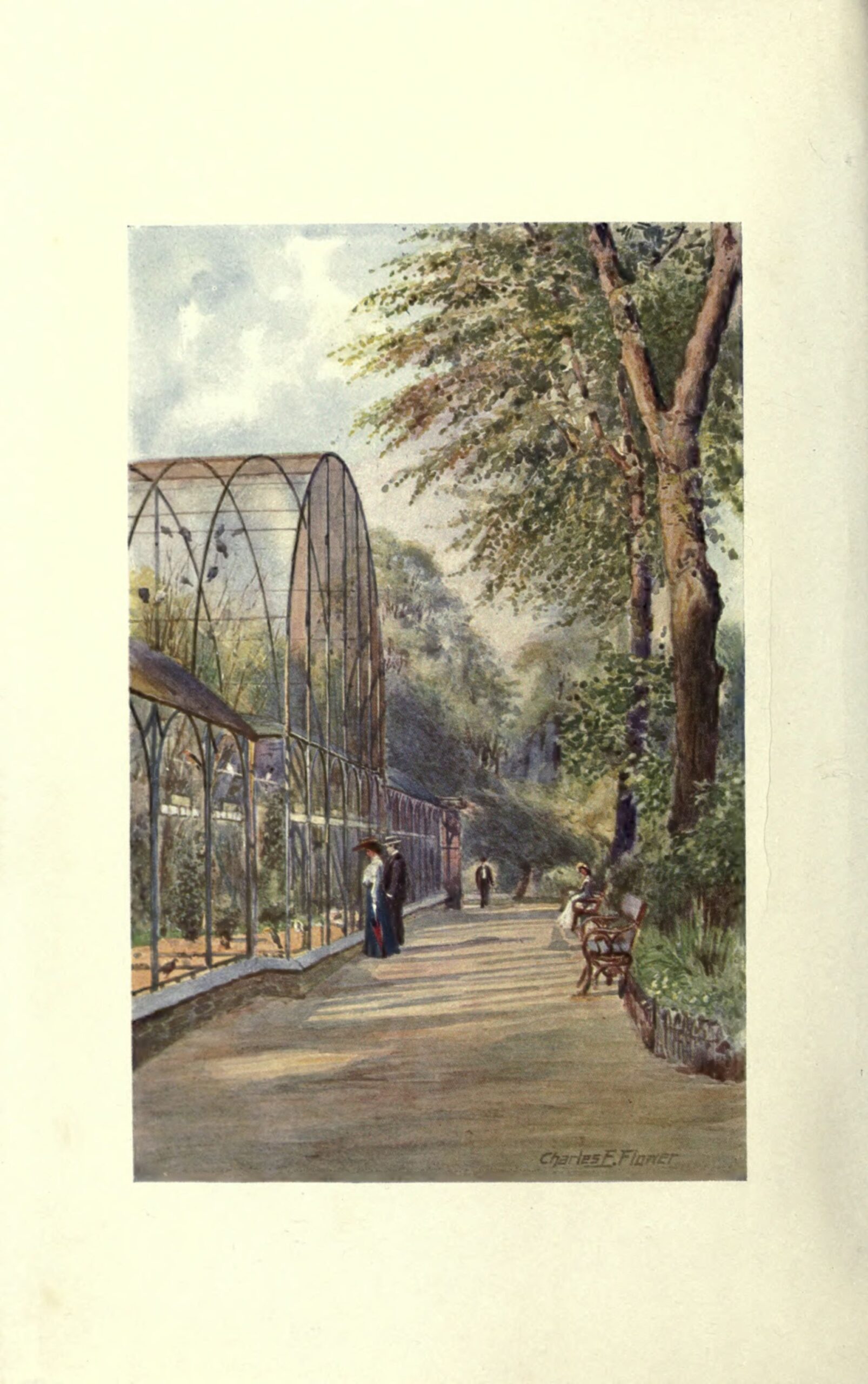

This book is copyright free and you can download it from this site The Zoological Society of London a sketch of its foundation and development, and the story of its farm, museum, gardens, menagerie and library 1905

This book by John Edwards is most informative and has images from 1852 up to 1914 of the animals and much more at London Zoo.

ISBN: 0952709902

Book on the history of The Zoological Society by Henry Scherren, printed 1905

Book on the history of The Zoological Society by Henry Scherren, printed 1905

This book is a culturally important record of the history of the Zoological Society and its menagerie in Regent’s Park, London.

Printed in 1905 and authored by Henry Scherren, FZS and Member of the British Ornithologists Union, the book sketches the foundation of the ZSL’s development and gives an overview of its farm, a museum at 33 Bruton Street (which in the early to mid-1840’s had Edward Gerrard as its curator), gardens and menagerie and was the first attempt to tell its story. (It’s generally accepted that the book’s index is incomplete and of limited value).

In the book, Mr Scherren also refers to the politics and jostling for position amongst the Fellows and appointed committee members. I don’t feel that this was a deliberate action on his part; he was merely recording in his book the factual goings on as evidenced by minutes of meetings. Some of the descriptions of the scenes between competing persons of note reminded me strongly that human behaviour is always and has always been motivated by five things: Pride, Recognition, Money, Love, Fear. The Pride and Recognition elements are clear and obvious in the descriptions of the attempts of some of the Fellows to out-manoeuvre each other!

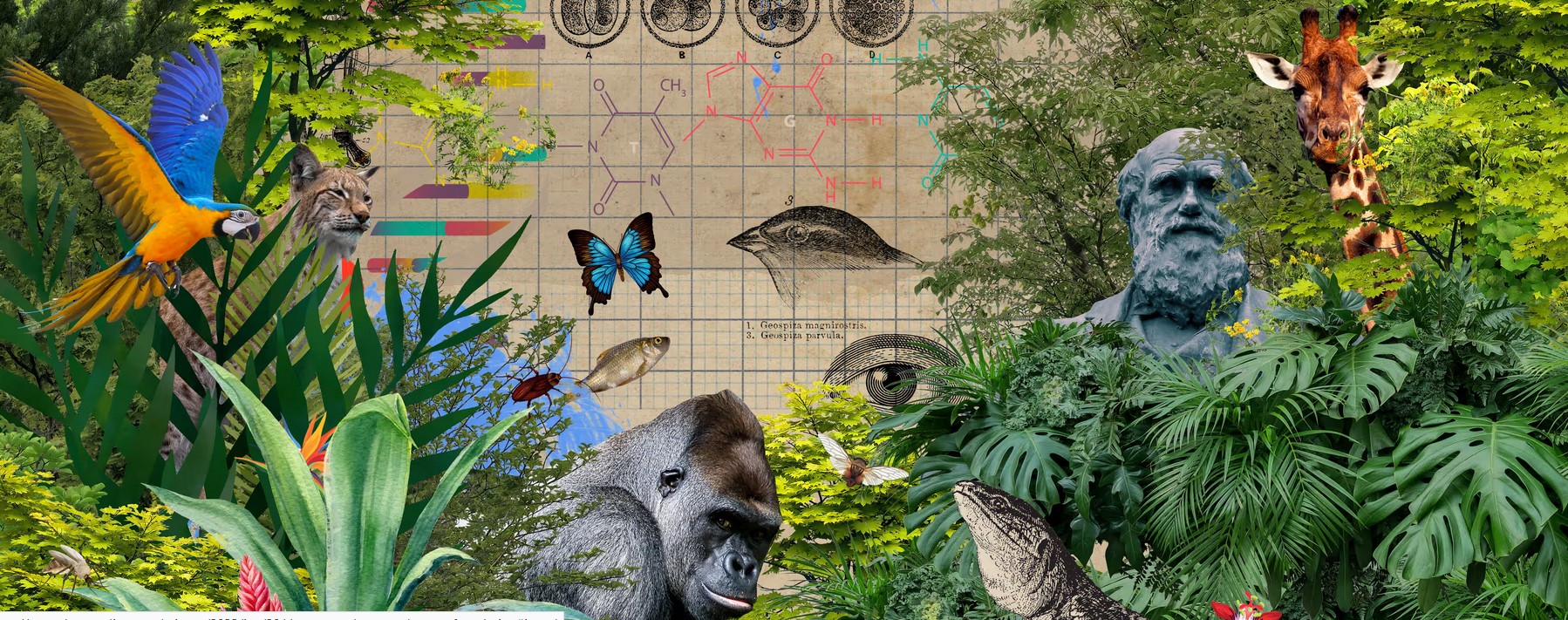

The ZSL - a scientific place for the study and nurture of natural history.

Most of the members of the ZSL, enthused by the natural science that had gripped the imagination of the educated throughout western Europe since the latter part of the 18th century had more personal objectives. For example, the distinguished surgeon Professor (later Sir) Richard Owen (1804-92) intended to spend all his spare time dissecting the dead specimens that were sent from around the world, as well as those that died subsequently in the menagerie. He wanted to know in detail how they differed anatomically.

The idea for a zoo in London, supported by a society to promote the science of zoology, was originally championed by Sir Stamford Raffles, who was elected the first president of the Zoological Committee in February 1826. His fellow council members included the earls of Darnley, Egremont, Malmesbury, the Bishop of Carlisle, Sir Humphrey Davey, the naturalist Joseph Sabine and the distinguished ornithologist, John Gould.

The ZSL’s stated purpose was to establish a scientific place for the study and nurture of natural history. Its key objective being to domesticate wild animals so that they could be studied further and bred. However, “vulgar admiration” was not at all on the agenda; it was an exclusive club set up by and for the higher and noble classes. It was hoped that Natural History could attain the same status and importance as Botany had done within the specialised association of the Horticulture Society.

The ZSL is an elite club

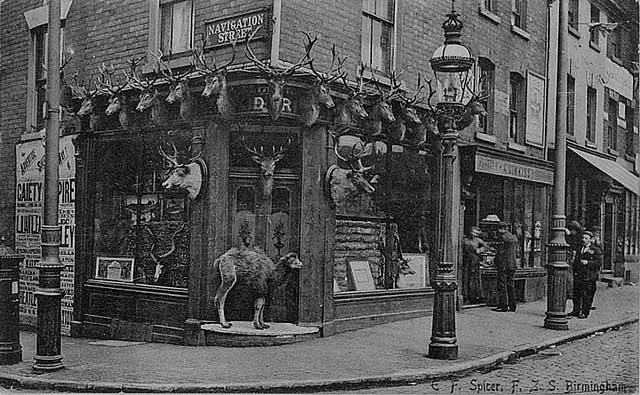

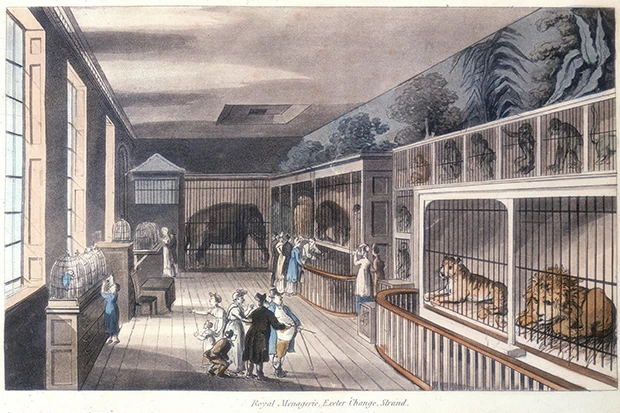

Before the ZSL flourished as an offshoot of the Linnean Society (founded in 1788), the only places that animals could be seen in Britain during the first quarter of the 19th Century were at the Royal Tower of London Menagerie, or at the Sandpit Gate at Windsor Castle, and at The Exeter ‘Change, near The Strand in London, owned privately by Mr T Cross who was an ex employee and son in law of the original menagerie owner, Stephen Polito.

Initially membership and connection to the ZSL was restricted to “Fellows” and the animal park menagerie was not open to the public. These “Fellows” came from the higher echelons of society, and they were the members and subscribers who provided funding and knowledge and helped to procure donations. In 1828 the public could only gain access to view the ZSL’s animal park if they could pay 1 shilling, but more importantly, if they had a written order from an existing Fellow. This was totally prohibitive to most people and so the public were effectively excluded, and it remained an elite club. It wasn’t until 20 years later in 1847 that the rule on exclusivity was dropped due to the need to raise money.

The public finally gained access for the price of one shilling at which level admission was to remain for almost a century (John Edwards 1996: London Zoo).

Animal Donations in the Early Days

Between 1827-1830 while the setting up of the ZSL ‘s menagerie was underway, initially the provision of animals came from people in the upper classes who had donated them after travelling the world to obtain them or ordering them from other travellers.

Initially, Mr Joshua Brookes from the Anatomical School in Blenheim Street first donated a Griffon Vulture and a White-Headed Eagle while Captain Pearl donated a female deer from Sangor. However, the ZSL had to outsource the keeping and management of these animals to the Tower Menagerie and the private Exeter ‘Change until the Regents Park site was ready.

Some animals were also kept at the ZSL Museum site in Bruton Street (which later moved to Leicester Square and later had its collection disbanded), including a cheeky “Wanderoo” Monkey who stole a visiting Bishop’s wig and refused to give it back. Before the Gardens were opened it is recorded that over 200 living animals were installed including Llamas, a Leopard, some Kangaroos, a Russian Bear, Emus, Cranes, Gulls and Gannets, and a celebrated Giraffe that had come from the Middle East.

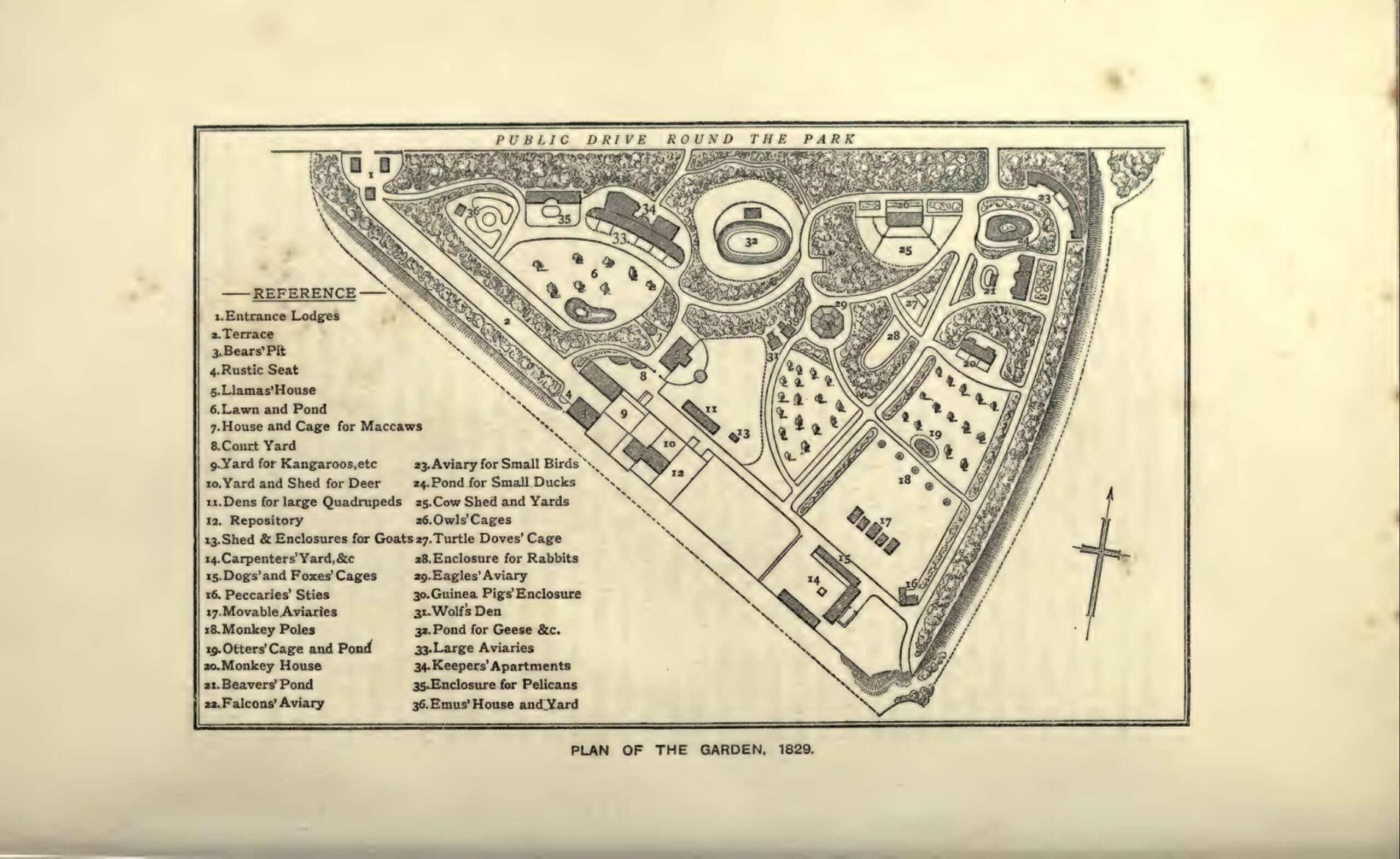

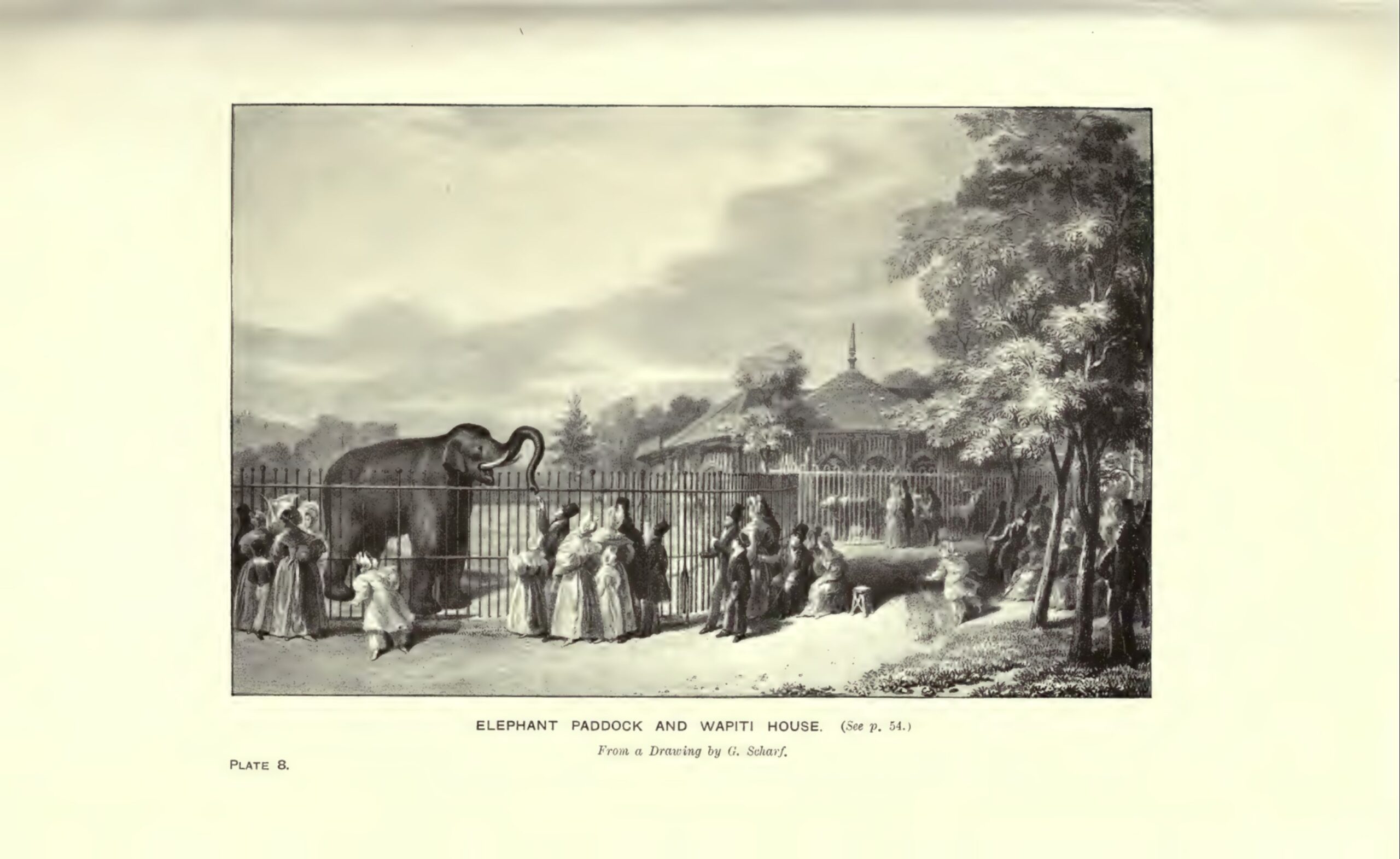

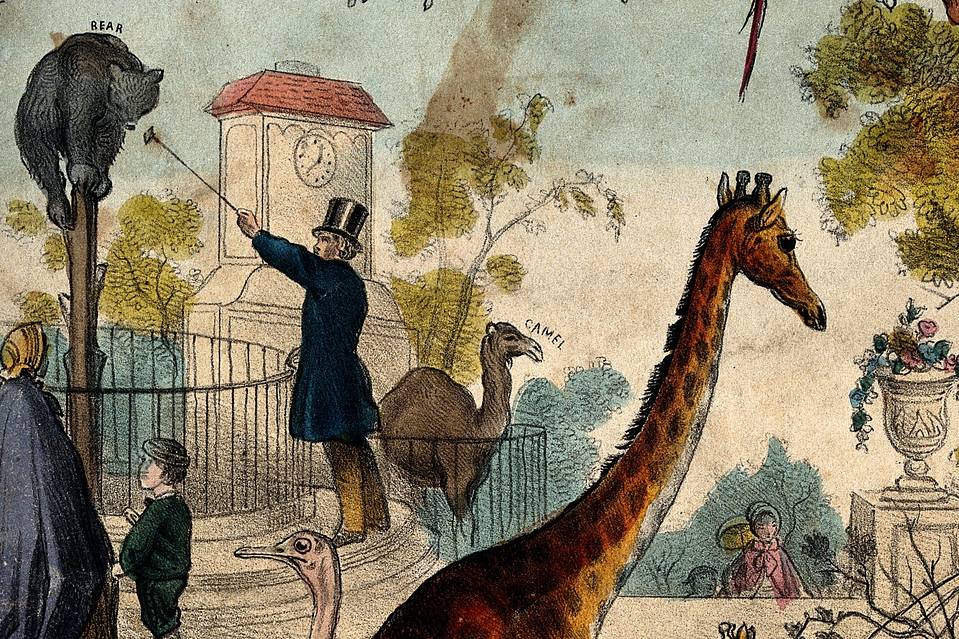

Once the Gardens were open in 1828 the visitor would pass by the main entrance where one would see a Bear Pit with three bears and a Llama House. Imagine!

At the South Entrance there were three Leopards, a Jaguar, a Lion Cub, two striped Hyaena cubs, a pair of Ocelots, a Civet Cat, a couple of Genets and some Porcupines. What a sight!

There were many other specimens dotted around the parks, including a Monkey House, a Duck Park and Eagles including Osprey and Bald Eagles and a Camel House.

In the 1830’s at the start of the ZSL’s journey, the Royal Menagerie stock from Windsor was donated. It is said that the King then became a patron of the ZSL.

I do not think it’s too far of a stretch of the imagination to think about how onerous it must have been for the Menagerie at Windsor to be maintained. Perhaps the Royals decided to rid themselves of the responsibility by donating their animals to the ZSL’s menagerie. It probably wasn’t even a question of money. It’s more likely to be a question of the increasing level of upkeep and skill and experience needed to look after all the animals.

This was also a key reason for many of the donations – the animals were being offloaded.

In 1829 His Majesty William IV donated a Giraffe to the ZSL’s menagerie that he had kept at Windsor. This Giraffe had just died, and it’s recorded in Sherren’s book that Messrs Gould and Tomkins dissected the Giraffe at the ZSL and His Majesty presented it as a gift. The taxidermy performed on the animal ensured that it was preserved and could be seen by a much wider audience – previously, due to its Royal location – very few people had seen it.

Between 1833-1837 one of the foremost zoologists of the time, John Gould, held the post of Superintendent of the Ornithological department of the Museum in Bruton Street before he left to go to Australia to complete his great work on birds.

From about 1830 many exotic animals came to Britain from all over the world, sent by Royal and upper social class Gentlemen-type travellers. Sent back from distant travels on ships, many of them died before or upon arrival, their diet and necessary environment were simply not understood well enough to ensure they thrived. Some of them were even stolen en-route. The ZSL Fellows worked hard together to improve conditions and understanding of their animals in the menagerie to ensure a better practical acquaintance about how these creatures could survive. They eventually learned that lions could withstand a certain amount of cold, but the care of a hippopotamus must have been a learning curve!

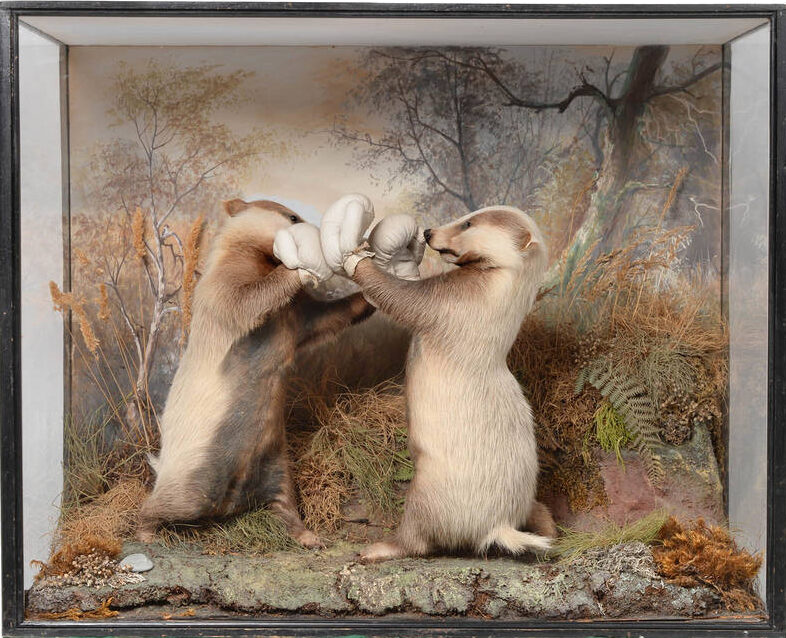

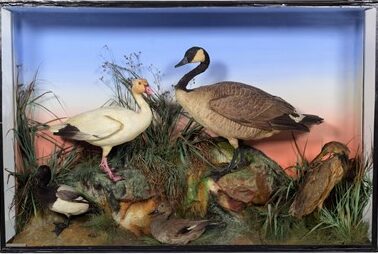

Taxidermy. Preservation. Public Display.

The Victorian Monkey Trade

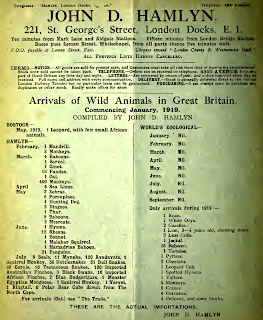

During the later Victorian period towards the end of the 19th Century, primates were arriving in huge numbers in Britain via the docklands in London and Liverpool, and the ZSL’s menagerie took many of them. They were imported as exhibits by hunters, royalty, travellers, and dealers. These dealers included the famous Jamrach and his famous rival, Hamlyn. These dealers had shops with yards at the back, sometimes three storeys high, that were packed with animals of every kind.

By 1890 the ZSL records a total of 2,256 animals in its menagerie.

Between 1883 – 1895 there were over 166 different species of primates at the zoo and the ZSL was taking in over a hundred a year.

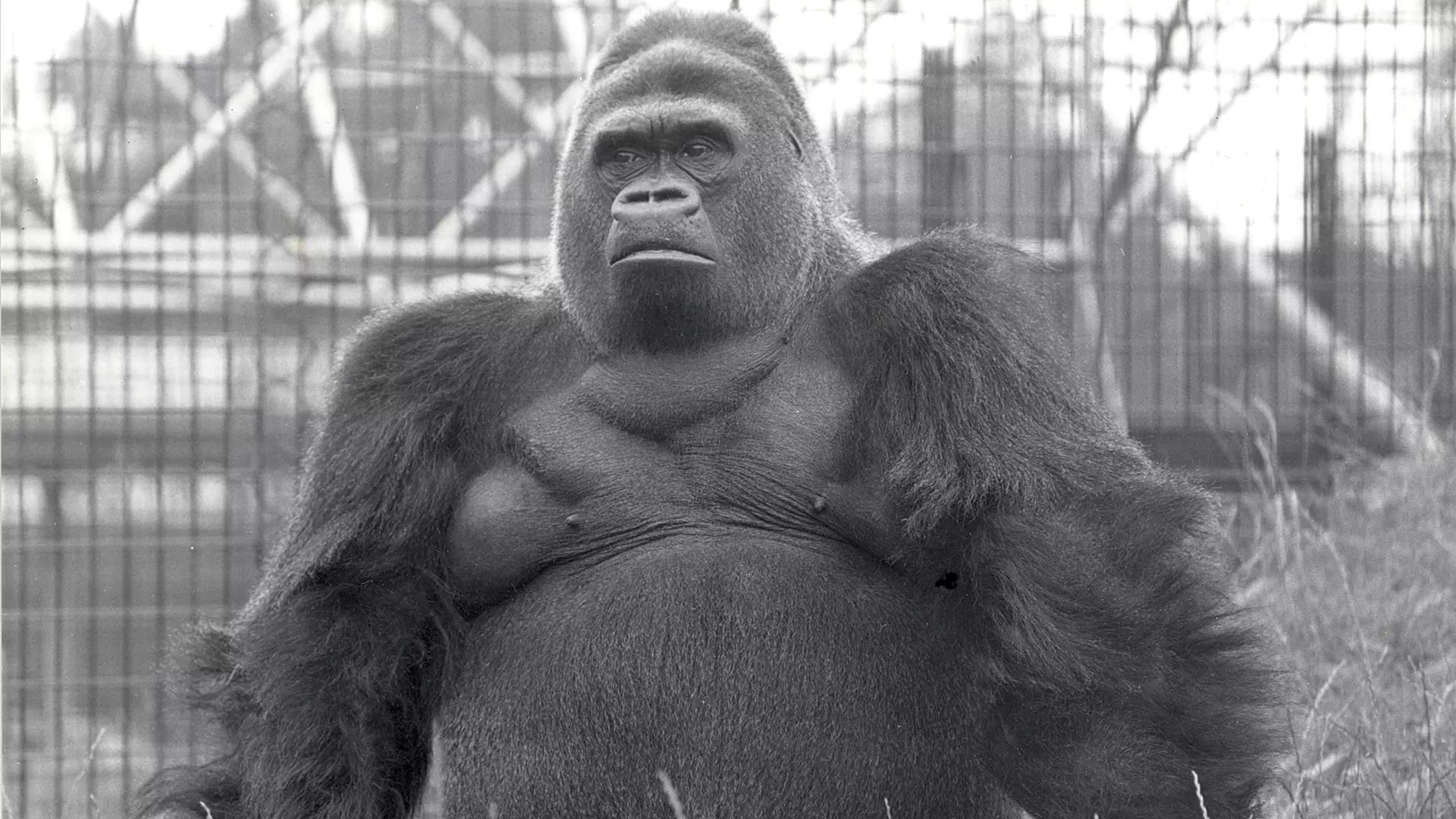

The primate population contained varieties of primate species and numbers, everything from a single Gorilla to over 100 each of crab-eating and Rhesus Macaques.

The zoo must have been packed, and the accommodation and funding needed to house them all surely must have been a significant problem. Some of them, as I saw for myself recorded in the Daily Occurrences and the Death Books at the ZSL Library were deliberately killed. This is denoted by K.B.O. in these books, which means “Killed By Order”.

After they were dead, they could be studied, and to do this they had to be dissected and their parts distributed to museums and medical schools. As well as specimens in whole or in part going off to be cut up and studied, some skins went to taxidermists including Edward Gerrard who already had strong ties to the ZSL and whose workshops were in Camden, a stones-throw from Regents Park.

Giraffes Parade Through London

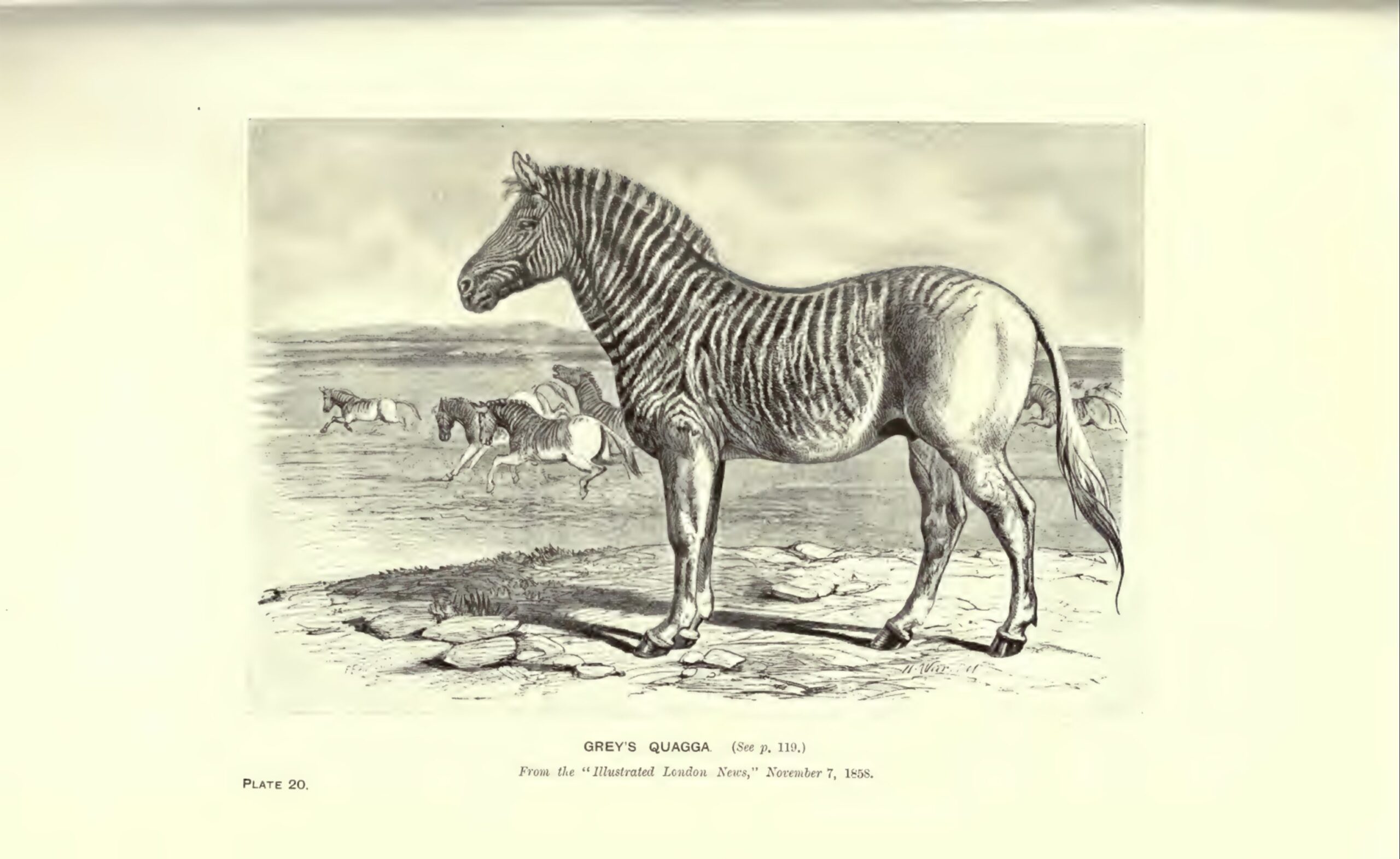

In 1831 it is recorded that a Quagga, A Moose Deer and an Indian Elephant were bought by the ZSL. In 1834 an Indian Rhino was bought for one thousand guineas, and in 1835 a Chimpanzee was imported from the Gambia, and it was the first such example to be displayed by the Society.

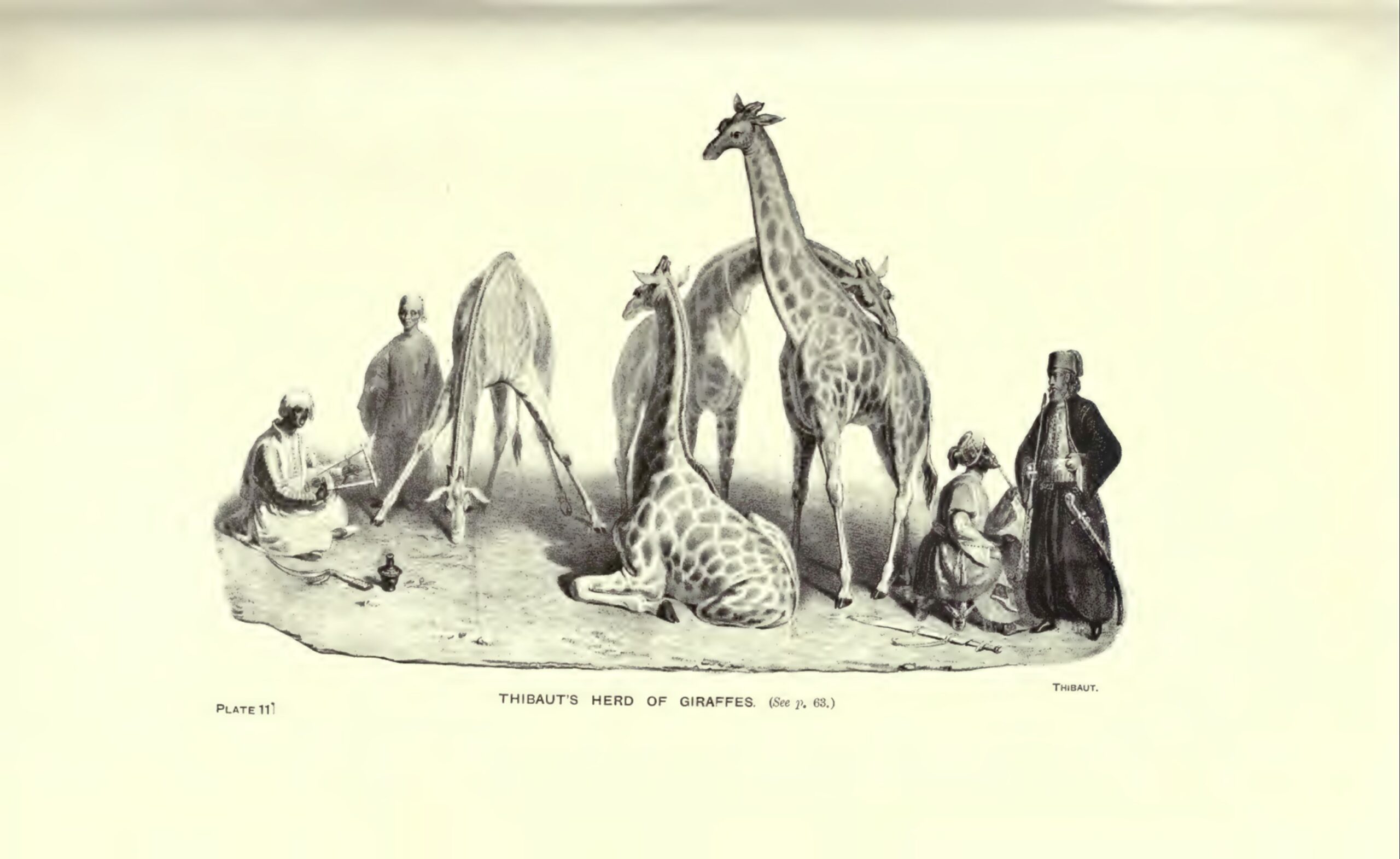

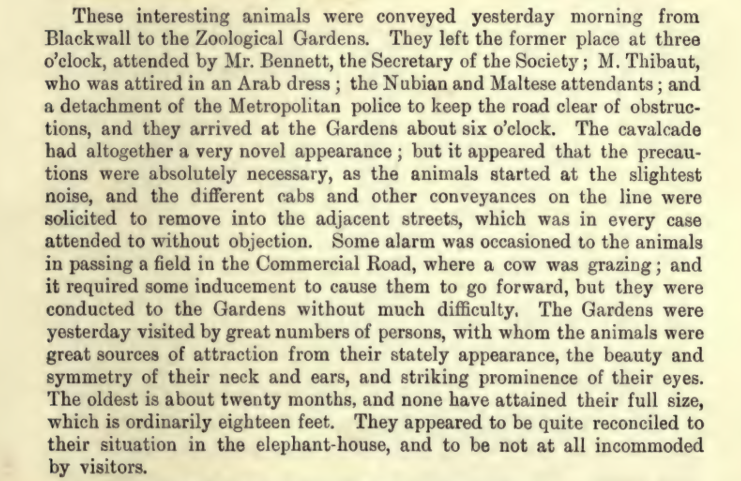

Animals were arriving at Britain’s ports on ships from all over the world and there are too many to list here, but in May 1836 the steamship “Manchester” arrived at Blackwall with an interesting freight that included a herd of Giraffes. Fellows and naturalists of the ZSL were waiting at the quayside, obtained the Giraffes and then had the problem of getting them through London to the Regents Park. The clipping describes the procession.

The evolution at the ZSL: The public are allowed entry

After the initial set up during the early years, money started to dwindle and expenditure year on year was increasing dramatically. Attempts were made to improve receipts including selling animals at the ZSL-managed Kingston Farm in 1834.

From 1841 there had been a gradual decrease in income and by 1847 it was obvious that something had to be done. The public were finally allowed into the ZSL gardens via a paid ticket, without an order from a Fellow.

Henry Scherren’s book describes in detail the animals that came to the ZSL menagerie throughout the ensuing years including from expeditions , from their own orders and from established menageries and from dealers such as Jamrach, and from Bostock and Wombwell’s menageries. These include Obaysch the Hippopotamus from the Nile that arrived in 1850 which proved a huge attraction for the crowds and reportedly Queen Victoria was very amused by it. There were also lions from Mesopotamia, Egyptian Snakes, Polar Bears and huge Tortoises and a pair of Thylacines from Tasmania.

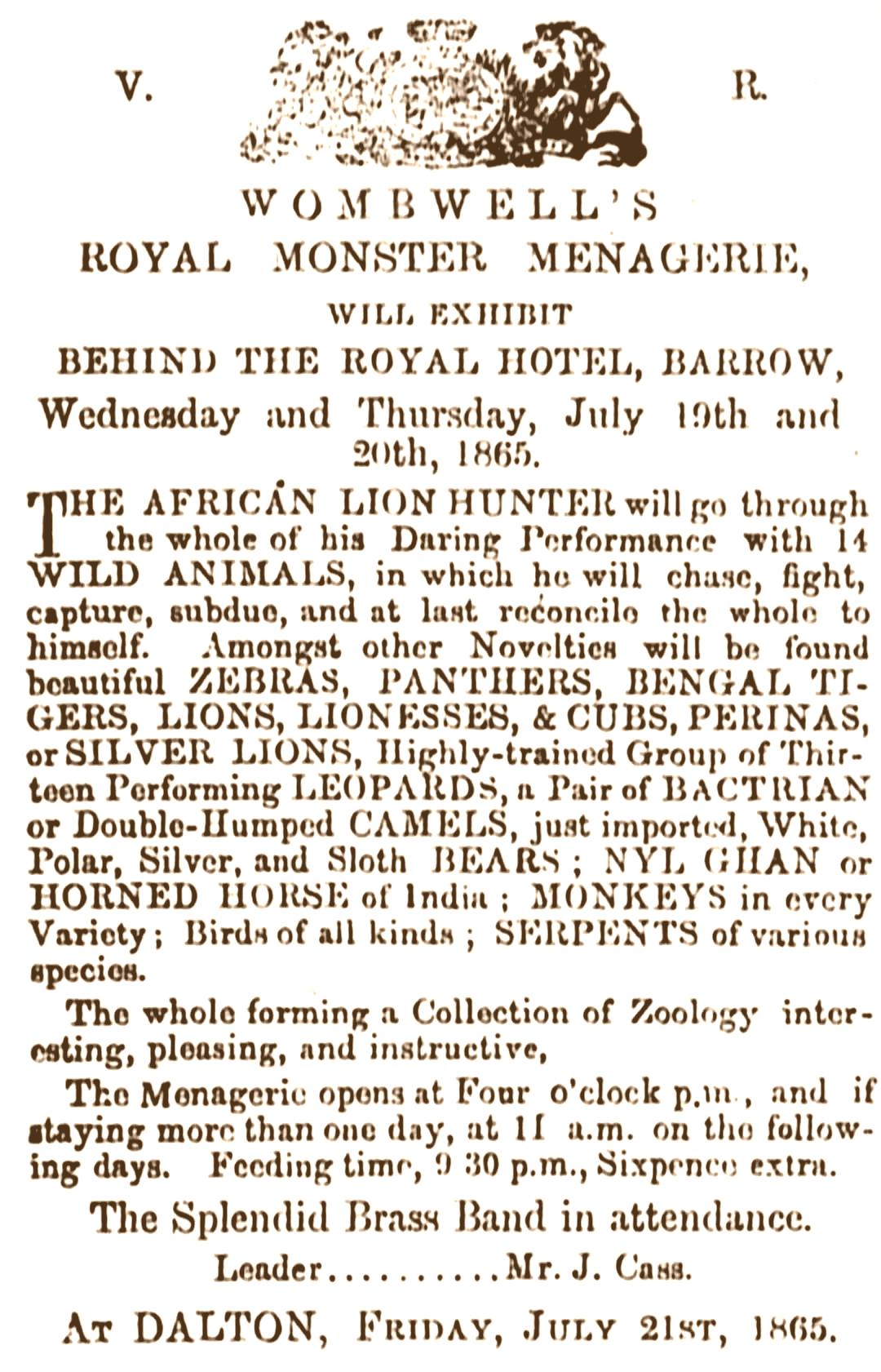

Wombwell's Menagerie

In 1865 the Wombwell’s menagerie was well established and toured Britain extensively, putting on shows and attracting huge crowds. (It would not become Bostock and Wombwell’s until 1867).

It was big business.

I found a particularly interesting advert for Wombwell’s show in my own hometown of Barrow in Furness.

At that time, there was plenty of land on which to display and house the animals. The subject of Bostock and Wombwell will be covered in a separate article.

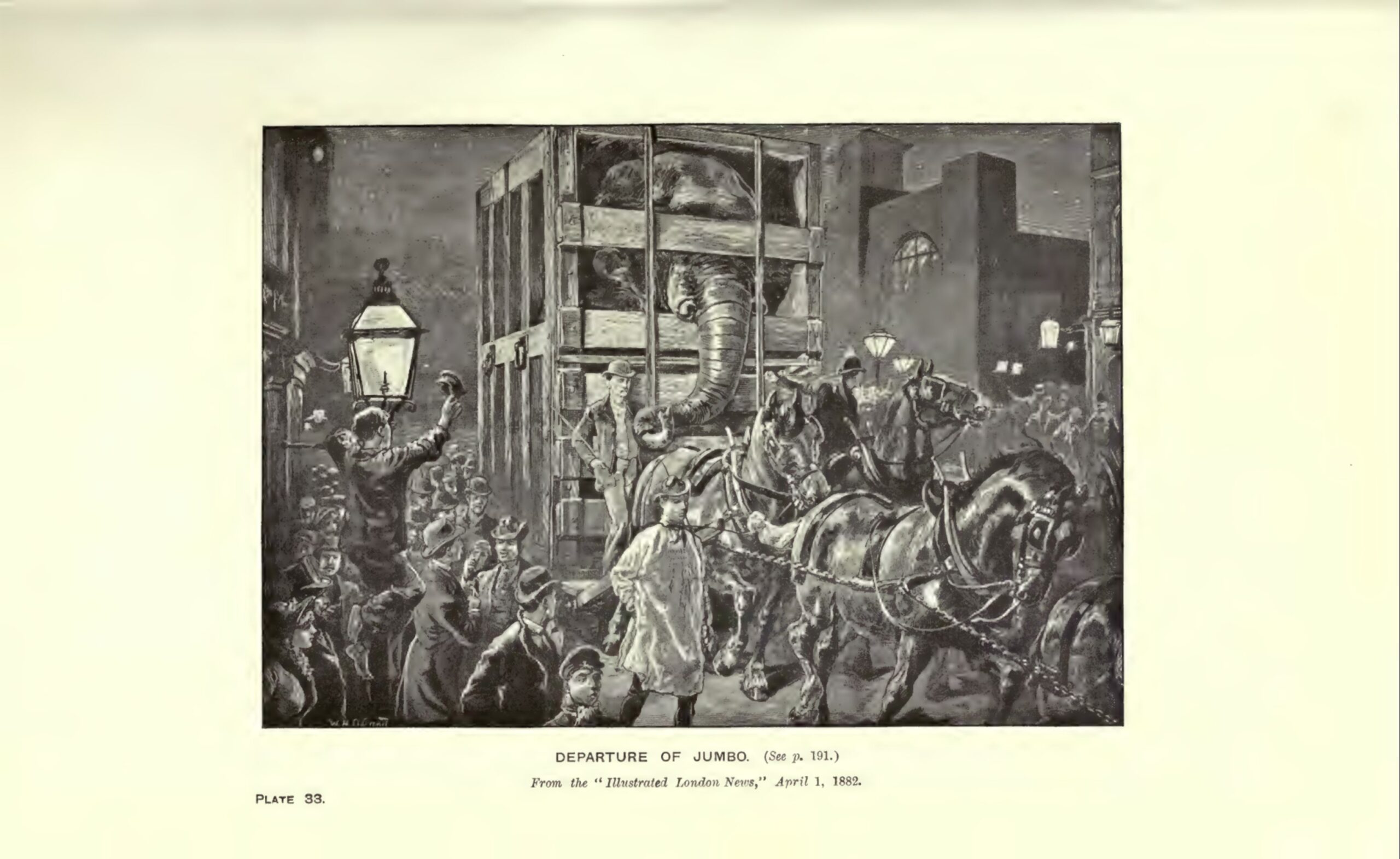

Jumbo is sold.

Abraham Dee Bartlett dies.

In 1872 the second Quagga to come into the holding of the ZSL was acquired from Mr Jamrach, the 19th century celebrated animal dealer and menagerie keeper. It was the last example exhibited in Britain. The celebrated naturalist and taxidermist, Edward Gerrard himself had later purchased it from Mr Franks of Amsterdam. Gerrard had remounted the skin and sold it to Baron Rothschild to place in the Tring Museum.

Jumbo the Elephant, a celebrity with the public, was sold to Barnum’s Circus in the USA in 1881 for £2,000 after it was considered that he had become dangerous. There was a big public backlash against the sale and the ZSL was accused of selling him like a slave, forcing him away from his habitat and the keeper that he loved. The sentiment is not wrong.

In 1891 the first Snow Leopard was acquired. He came from Bhotan and was considered to have completed the collection of big cats. Unfortunately, he lived for only a short time. I mean, how does one look after a wild Snow Leopard?

Abraham Dee Bartlett (1812-1897) who had previously been a taxidermist and small animal dealer, and who after the Great Exhibition of 1851 had worked with the animals at the Crystal Palace (moved from Hyde Park to Sydenham) had become the Superintendent at the ZSL in 1859. He died in 1897 at the age of 85yrs after 38 years’ service, succeeded as President of the ZSL by the Duke of Bedford of Woburn Abbey. Although Bartlett was a self-taught taxidermist, he had previously won prizes and high esteem at the Great Exhibition of 1851, and he had connections with Queen Victoria whose pet bird he took care of during her absences from London.

The Windsor Menagerie is joined with the ZSL Menagerie

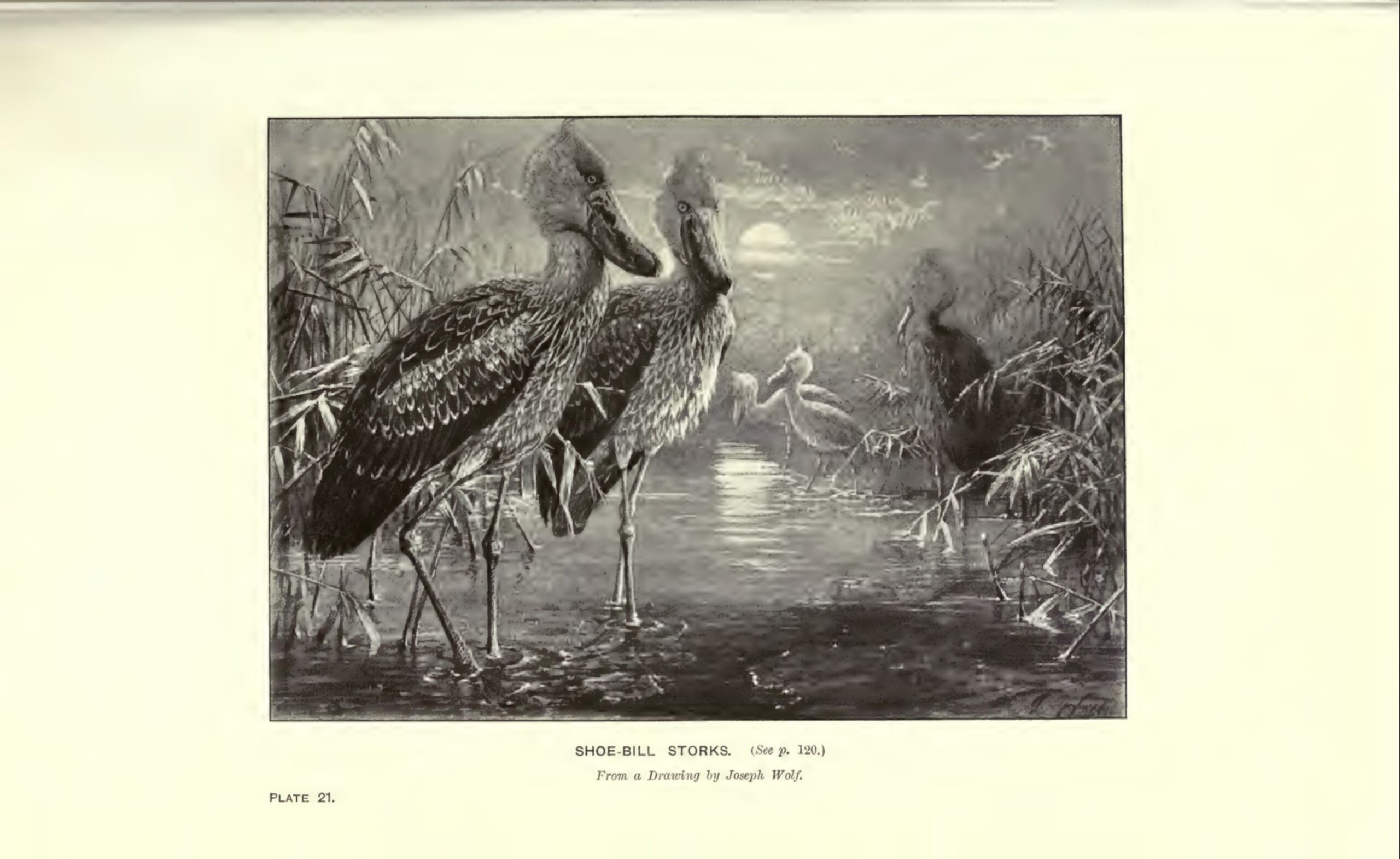

In 1897 £3,400 was spent to open the Ostrich House. Apart from Ostriches it contained Rheas, Cassowaries and Emus, Cranes and Storks. In the same year, Hon Walter Rothschild of Tring donated £150 to open the Tortoise House which contained a gigantic Daudin’s Tortoise. Rothschild was known to admire any creature of gigantic size and had a particular penchant for the tortoise. In 1899 the Zebra House was finished at a cost of about £1,100. A bargain.

In 1901 Grant’s Zebra arrived and was the first of its kind to reach England, after it was presented to His Majesty the King by the Emperor Menelek of Ethiopia. It was like a Burchell’s Zebra but didn’t have the same type of stripes. At the same time the Royal Menagerie at Windsor was broken up and all the animals were sent to the ZSL menagerie. The animals included 2 Spanish cattle, 1 black faced Kangaroo, 1 yellow footed rock Kangaroo, 1 Grevy Zebra, 2 Somali Ostriches, 1 American Bison, 3 Zebus, 3 St. Kilda’s Sheep and 3 Nubian goats.

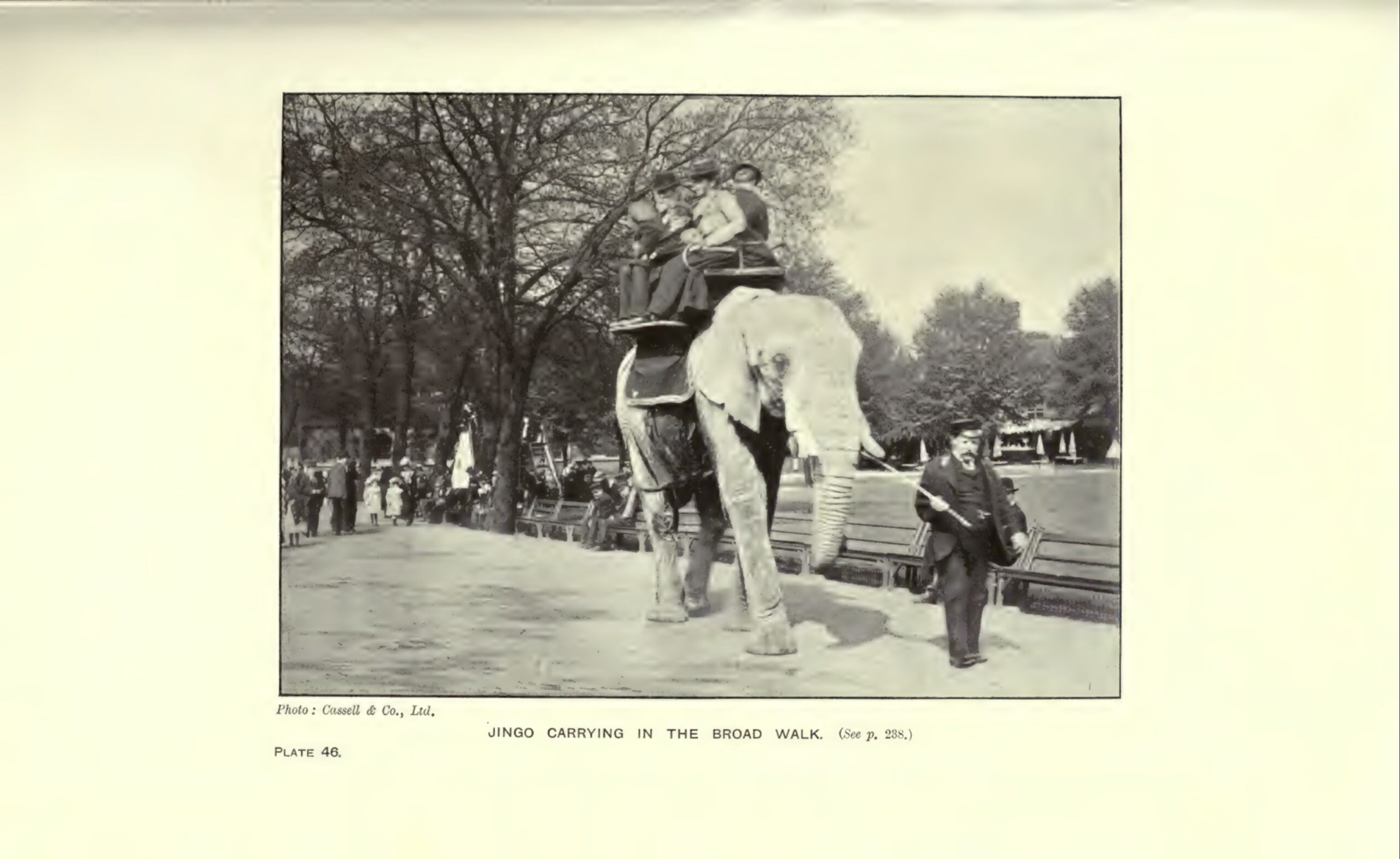

In 1903 Jingo the Great African Elephant whose behaviour had become difficult, was sold to Bostock in the USA for £200, just like Jumbo had been previously. Jingo was sent on a train to Liverpool and then boarded the ship “Georgic”. Tragically, he died at sea. I don’t know if Bostock paid the fee or whether they got a refund; either way, it’s cruel and sad.

From sad pawns to conservation

Overall, losses and deaths from the opening in 1828 right through to the turn of the next century at the menagerie happened often. Learning about how to provide the correct habitats and health management did not come overnight. Until the early 1900s the ZSL did not have a record of veterinary care on the site, and it was said that the keepers exploited and teased the animals by making them perform tricks for money.

How could the society possibly recreate the habitat and living conditions of animals that had never been seen in Europe before?

How could they possibly make a good environment for a polar bear, for example?

Efforts were made under scientifically motivated postmortems to find out the causes of some of the deaths. A polar bear that died suddenly at the menagerie in 1903 was dissected and found to have suffered an aortic aneurism. The Royal College of Surgeons already had comparable examples that it had collected over the preceding 70 years or so and these were presented to the Fellows at a meeting in 1904.

By the early 1900s the Society held a strong equine stock. There was a desire to “do something” with them, rather than allowing them to languish in “masterly inactivity”. The Zebras were thought to be capable of being trained. Hon Walter Rothschild had a team of Zebras and was seen regularly to drive them through the streets of London. Mr W. Simpson Cross, the dealer was also frequently seen trotting out a team of Zebras through the Liverpool traffic, bridled like horses, while in Paris, a team from the Jardin d’Acclimatisation were also seen trotting along the streets through the traffic.

The animals that had been plundered from their habitats and sent from exotic places across the world were in fact essential, but sad pawns in the development of scientific knowledge.

THE EVOLUTION OF THE MODERN ZOO

From the cabinets of curiosities which emerged from the 15th century onwards, then to the landscaped parks of nobility with their bourgeois zoos in the 17th and 18th centuries, then the travelling menagerie in the 19th century which reached the wider public, and then the ubiquitous carnival of fairs and circuses in the 19th and 20th centuries – the modern-day zoo tells a story of its own evolution.

Through these mutations finally the zoo has become a place for education and science and conservation, not for the wonder or freakery (and cruelty) previously found in menageries, carnivals or fairs.

These days the ZSL’s raison d’etre is conservation.

ZSL is working in more than 50 countries around the world to protect animals and their habitats: from protecting hedgehogs in Regent’s Park and marine life in the River Thames, to the far-flung corners of the Mongolian desert and depths of the ocean.

They run educational programmes and workshops, master’s and PhD courses and awards are provided to support young conservationists.

Thankfully, it’s all a very far cry from the exploitation of the 19th century when Giraffes and Zebras were walked through London and Elephants were sent on trains.

The Archives of the ZSL and The Menagerie

The archives of the ZSL are found in the Library of the Zoological Society of London and contain a range of records that are of interest to researchers. You must make an appointment in advance if you want to go along and research any of the archive material.

The Death Books

One of the most interesting set of records is the Death Books ranging from 1872 to 1899. These contain daily records of which animals had died, where they had originally come from and how they were disposed of. You will find historic names in these books: Rothschild, Gray, Gould, Gerrard, and the Earl of Derby included.

These Death Books proved extremely interesting to me when I was researching the source of the three Scarlett Ibis in a cabinet by Edward Gerrard. Looking through those records I saw that it was highly likely that Ibis from the ZSL in either 1872 or 1877 that had been given to Mr Edward Gerrard had been used to create this wonderful cabinet.

If you want to search the archives in advance of deciding whether to visit the library by appointment, then you can search here:

THE BOOKS OF THE DAILY OCCURRENCES

The Books of the Daily Occurrences

These historic record books are a general record of the happenings at the two zoos in London and Whipsnade. They were completed daily, and they list the arrivals and departures, births and deaths of animals at the two zoos.

Other details mentioned in some of the books are the number of visitors and money taken, the names of some high-profile individual visitors, the absence of keepers, a list of unwell animals, notes on building works, and notes on the temperatures in the animal houses, and the weather.